Tilbury Fort has been defending London from the threat of invasion for over 500 years. Since the fort was built in 1539, under the rein of King Henry VIII, it has survived many wars and battles including the Spanish Armada. At its peak in the 1700’s there was an estimated 100 guns at the site.

In 2014 Beyond the Point was invited by English Heritage to go to a special behind the scenes tour of the site, which we filmed in our video below.

Please note that this video was filmed in 2014 and therefore may not be up to our current standards.

The Thames was a strategically important location, responsible for protecting London and the royal Docks at Deptford and Woolwich which carried 80% of England’s exports. There have been forts at Tilbury as early as the 14th and 15th centuries, although little is known about their design but it wasn’t until Henry VIII became King that the defences were significantly improved. Under the King’s new programme of work, the Thames was protected with a network of forts scattered along the river, including one at Gravesend.

West Tilbury Blockhouse, was initially called the “Thermitage Bulwark”, because it was on the site of a Monastery sold off by the King in 1536. The cost of this was £211, which included 150,000 bricks and 200 tons of chalk. The D-shaped blockhouse was curved at the front, with two storeys of gun-ports and ancillary buildings were placed at the rear and the whole site was protected by ditches and the marshland creeks. Armed with up to five artillery pieces the invasion threat passed and in 1553 all of the blockhouses were ordered to return their guns; Milton and Higham forts were demolished.

In the summer of 1588, however, there was a fresh threat of invasion by the Spanish Armada. Yet again, an army was mobilised to protect the mouth of the estuary and emergency improvements to the fortifications at Tilbury were made. Queen Elizabeth I visited the fort by barge and gave a speech at a nearby army camp. Fears of invasion continued even after the defeat of the Armada.

In the early 1600s, England was at peace with France and Spain and the coastal defences received little attention with multiple problems occurring at Tilbury due to neglect. After Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, coastal defences were put back in the spotlight. The Dutch fleet then attacked up the Thames in June 1667, but according to reports, were deterred from going further for fear of the Tilbury and Gravesend fortifications. In reality, the forts were poorly prepared to resist a Dutch attack; with Tilbury only equipped with two guns. The Dutch struck the English fleet at Medway instead, giving enough time for the government to improve the defences along the Thames and mount 80 guns on the forts. In the wake of the conflict, the King instructed his Chief Engineer, a Dutchman called Sir Bernard de Gomme, to develop Tilbury Fort’s defences further.

De Gomme prepared several plans for the King in 1665 and work quickly began but took until 1685 to complete. Up to 256 workers worked on the fort. The total cost of the project is unknown, but was significantly more than the original estimate of £47,000. The result was a large, five-sided, star-shaped fort with an outer curtain of defences, including two moats and two new gatehouses. Two gun platforms, stretched alongside either the side of the fort. The interior of the fort was raised up above the level of the marshes to prevent flooding, and barracks and other buildings were constructed inside. By the start of the 18th century, Tilbury Fort was one of the most powerful in Britain. From 1716 onwards, it was used as a gunpowder depot; due to safety restrictions on moving gunpowder in and out of the London docks. Two large magazines were built (featured below) and the old blockhouse and other buildings were converted to act as further magazines. Eventually the fort could hold more than 19,000 barrels of gunpowder.

During the American Revolutionary War there were fears of a French attack on London so the Army decided to carry out a practice attack on the fort using 5,00 soldiers. Many of the guns were discovered to be inadequate so a new battery was built armed with 32-pounder guns pointing down-river, and a new battery, New Tavern Fort, was built directly opposite, on the other side of the river. Naval and defensive technology continued to improve over the next few decades with Tilbury Fort soon becoming outdated.

Other defences along the Thames were deemed sufficient and improvement works at Tilbury Fort were ceased for the near future. Torpedo boats and armoured cruisers were the latest threat at the start of the 20th Century and in 1903 four quick-firing 12-pounder guns were added to Tilbury Fort, in addition to two 6-inch guns the following year, but in 1905, the government and the Royal Navy decided that other forts gave sufficient protection for the capital and removed the artillery, leaving only machine-guns in place.

After the outbreak of the First World War, it was used to house up to 300 transit soldiers and to supply the new army camps built nearby. Electric lighting was installed, and a narrow-gauge railway and a steam crane on the quay were added to help move ammunition. During the inter-war years, the government concluded that the fort was no longer militarily useful and there were unsuccessful attempts to sell it off for development. During World War Two the barracks and facilities block were bombed and damaged, being demolished after the war. The fort was transferred out of military use quickly after the war and restoration work took place in the 70’s and was opened to the public in 1982. Today the site is run by English Heritage who gave us this special tour of the site. The fort is in fact protected under UK law as a scheduled ancient monument and the officers’ barracks are grade II listed.

Demolished Barracks

Officers’ Barracks

Magazines (open to the public)

Exclusive Tour – January 2014

In 2014, we were very lucky to be shown around the fort in its entirety including parts usually off-limits to visitors thanks to Kevin Diver from English Heritage for inviting us.

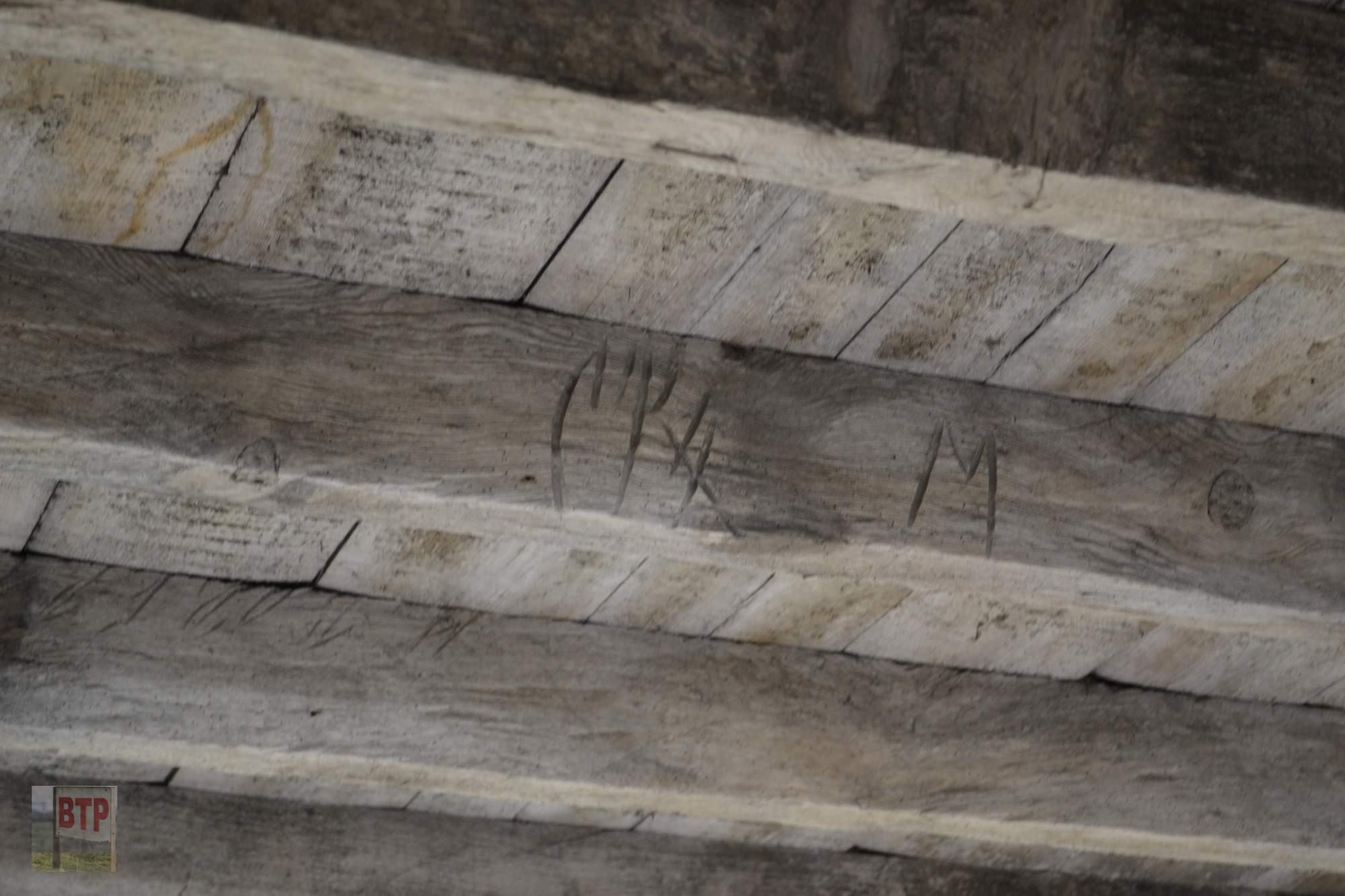

Kevin started by showing us the Dutch style bridge connecting an islanded protrusion – the Ravelin, which would have originally led into the fort. The replica from 1980 was based upon original plans. Whilst the bridge is more than safe for regular tours, it’s currently unsuitable for frequent access. The Dutch are known for their drainage with most of the current drainage on Canvey Island still based around Dutch designs. As most of the land at Tilbury Fort was reclaimed marshland, drainage was a priority and the photos below of the bricks was part of a mound that was built. This would have also contained gates for people who were entering the fort through the bridge.

Next we took a look at the defences that the fort offers, including the wall that surrounds the fort. This was actually lowered at one point so that the officers and their wives could see out of the fort! The Home Guard installed two Spigot Mortars during the Second World War. Both bases remain at Tilbury Fort, with a replica Spigot Mortar on one of them.

We next went into the ‘Dead House‘, a room with a trap door used to store the sick and injured as a kind of quarantine – it was either die or recover! It was later used as a dormitory and also for storage.

By the First World War, anti-aircraft guns were added, and shot down a German zeppelin. This was the only time the fort actually had any military success throughout its long history. Of course, we must remember that if defences such as Tilbury Fort were not built throughout history, the country would be allowing enemy invasion. It could be said it acted more so as a deterrent. The 18th Century barrack blocks were damaged in the Second World War, and were demolished in 1950.

The original 400 year old explosives Magazine from 1685 was later connected by a tunnel system added later in the Victorian era, featuring two cartridge lifts on the way. There several Victorian magazine tunnels around the site, but this was one of the most special leading to one of the oldest parts of the fort. Whilst some are open to the public, quite a lot is off-limits due to health and safety, so we were very privileged to be allowed a look at this. A lot of the tunnels have severe cracks in the wall and are supporting by aged scaffolding. Below are images of the Victorian tunnels and cartridge lifts, with the large chamber they led to being the 1685 magazine.