Ordnance Survey 1945-1965 mapping showing the five Epsom Cluster asylums

In Epsom, Surrey, the former London County Council decided to create five London County Asylums as suburban mental hospitals. These were mostly typical ‘lunatic asylums’ as they were initially known – large institutions to accommodate those with mental illnesses, disorders and learning difficulties. The Manor (1899), Horton (1902), Long Grove (1907), and West Park (1924) were all conventional asylums, although the Manor became a certified institution after WWI for those with learning difficulties, and West Park was named a mental hospital rather than asylum due to its later opening. The fifth hospital; St. Ebba’s (1904), initially opened as an epileptic colony, representing another twentieth-century attempt to provide more specific care, although eventually evolved into a mental hospital and learning difficulty institution like the others.

Most of the Epsom Cluster hospitals closed in the 1990s, when other institutions across the county were closed in a shift towards the care in the community approach following declining conditions. However, the NHS still runs smaller facilities at West Park, Horton and St. Ebba’s. Otherwise, they have all fallen to demolition or been partially converted into residential properties. Many of the hospitals fell into dereliction by the millennium, and became favourites of urban explorers who now provide one of the few detailed visual records of the former hospital buildings – especially West Park. Beyond the Point was too young when these hospitals were still abandoned to visit them, but in 2024 we sought to document the surviving and converted structures. In contact with the Friends of Horton Cemetery Charity and former locals and explorers of the hospitals, we have created this article to record the Epsom Cluster’s modern legacy.

The hospitals during dereliction, courtesy of TheTimeChamber. Pictured is West Park’s admin block, a ward and an original padded cell, and St. Ebba’s recreation hall.

The Manor Hospital

The Manor Hospital was the first built in Epsom by London County Council, marking the start of the cluster when London County Council bought the Horton Manor Estate. The Manor Hospital was developed around the pre-existing Horton Manor House around 1896-1899, under the design of William C. Clifford-Smith. Initially, 700 harmless chronic female patients were accommodated in wooden huts on the Manor’s grounds. This was close to where the current Old Moat Garden Centre & Cafe is today; an excellent charity helping people with mental health issues today. Over the following decade, a permanent sprawling asylum building was added behind the manor house. The asylum building was increasingly expanded to form a sort of L-shaped plan. Because it developed more organically than most asylums, it did not follow a regular plan, although arguably falls into the corridor plan category with wards extending from a linear corridor.

It saw brief use as a war hospital from 1916, and after West Park Hospital opened in 1921 it changed roles from a mental asylum to a mental deficiency colony, as efforts were being made nationally to separate the mentally disabled from the mentally ill. The wooden huts still remained in use into the 1970s when they were redeveloped, with the main asylum building closing in 1996 and subsequently being largely all demolished.

The Manor house, seen above in its present residential converted state in 2024, appears to have been heavily rebuilt following damage by wartime bombing. It is one of the very few surviving parts of the hospital today.

Horton Hospital

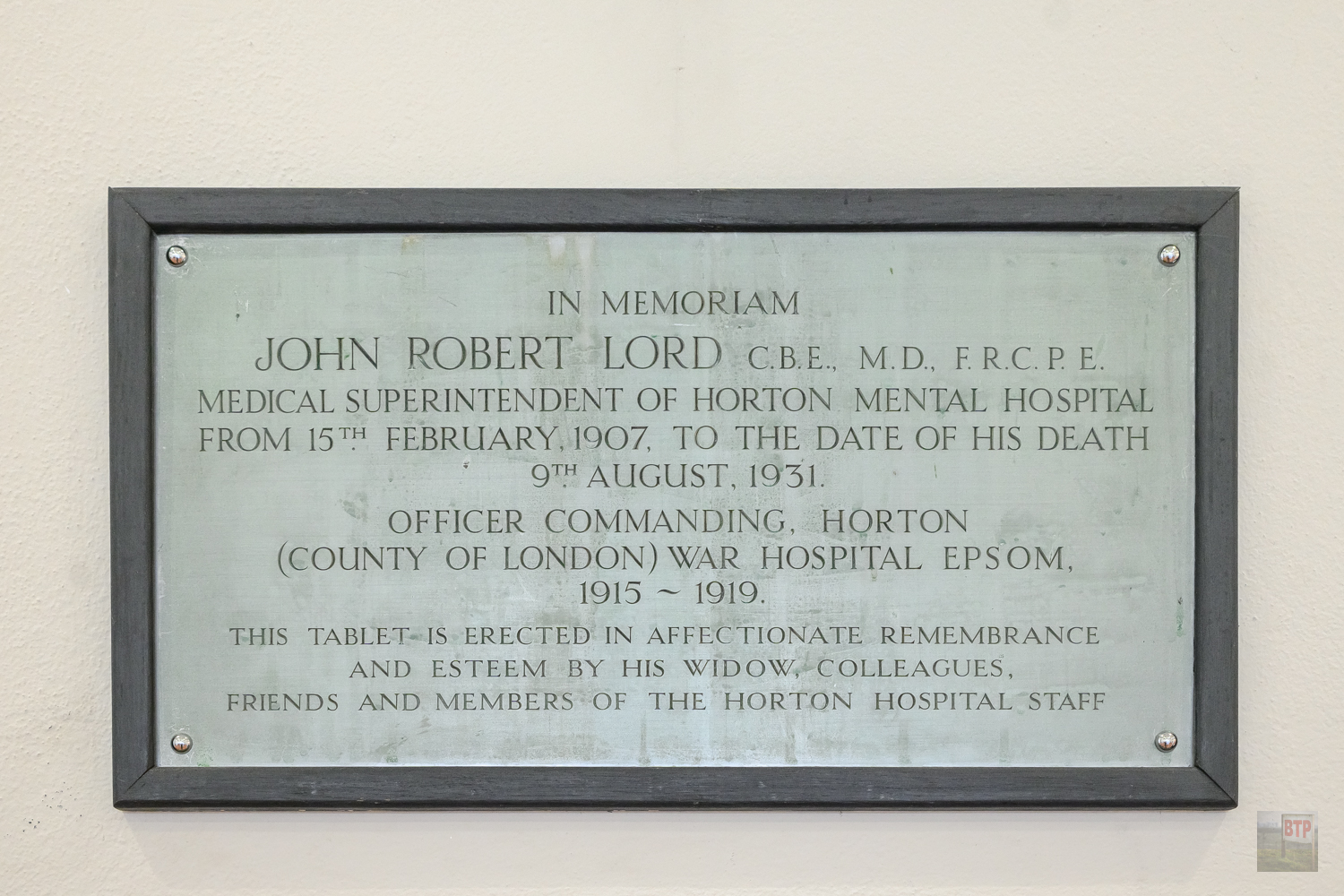

Aside from The Manor hospital which evolved over time, the Horton Asylum was the first planned mental hospital at Epsom, built in the conventional compact arrow echelon plan, pioneered by its nationally-renowned designer George T. Hine close to the turn of the twentieth century. It was modelled on the asylum at Bexley. The asylum is visually distinctive for its use of yellow brick, created from clay dug in excavations of the building’s foundations. Work began in 1897, but efforts were diverted to The Manor’s more temporary forms of accommodation. Horton was finally opened in 1902. It served as a War Hospital from 1915 to 1918, and changed name to Horton Mental Hospital thereafter. From September 1939 to October 1947, it served again as a War Hospital. It closed in 1997, with its main building being largely demolished and partially converted into residences, although small peripheral parts remain open to this day.

The hospital was known for pioneering malarial therapy for patients suffering from general paralysis; now known as neurosyphilis, a fatal development of the venereal disease rife at the time that attacked the brain. Patients would be placed in a room where a single malaria-carrying mosquito was released, biting the patient. This would induce a heavy fever which would kill syphilis bacteria in those that survived, but some would not survive the treatment.

Below is the original administration block of Horton Hospital with its distinctive pale brick and red brick striping. Relatively plain in decoration compared to some. This forms part of the main hospital site now largely demolished and converted to residences.

Below is the small section of Horton Hospital still in use by the NHS. It exists south of the main building and chapel, and comprises two ward blocks known as Horton Haven, which probably formed the original admissions block, and the gate lodge.

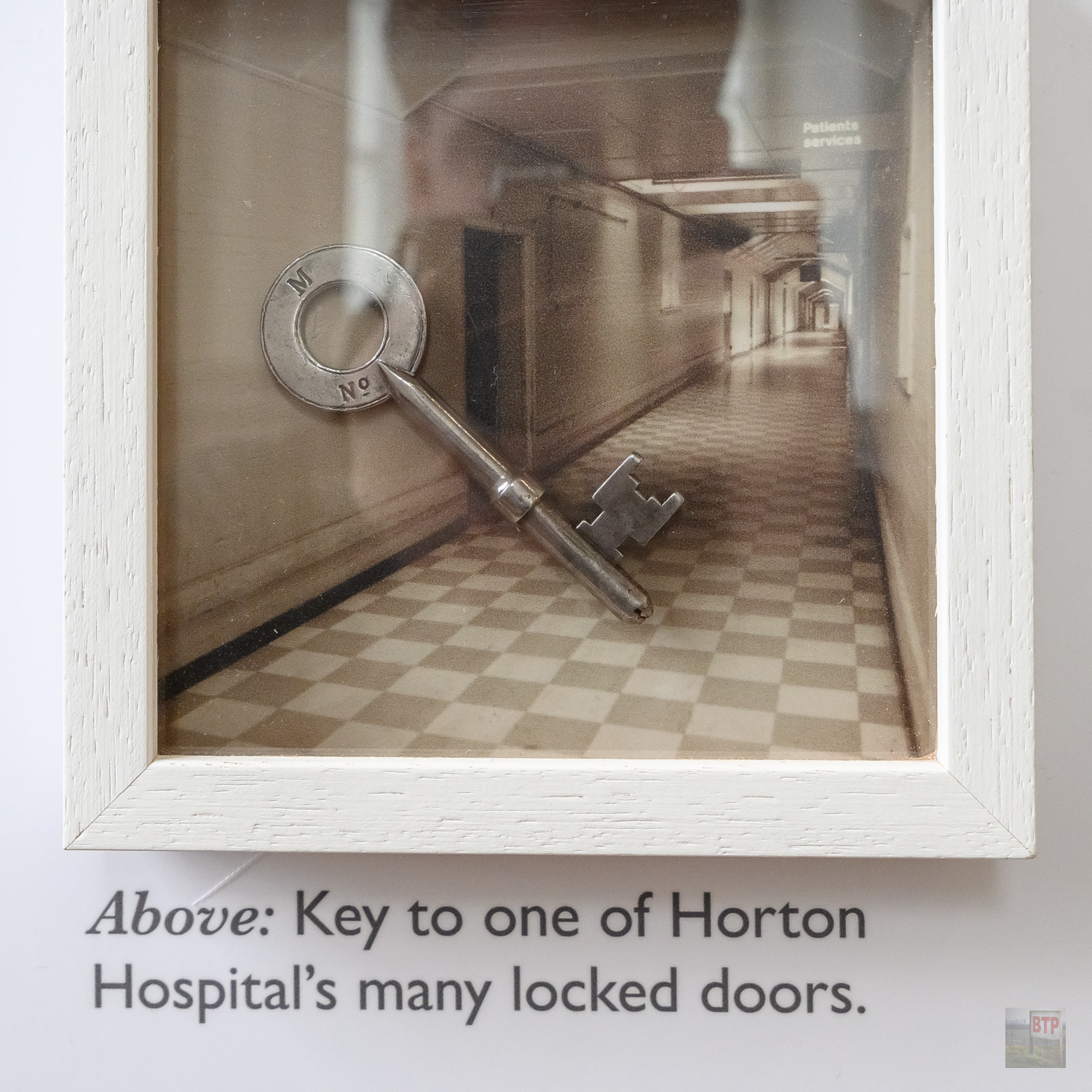

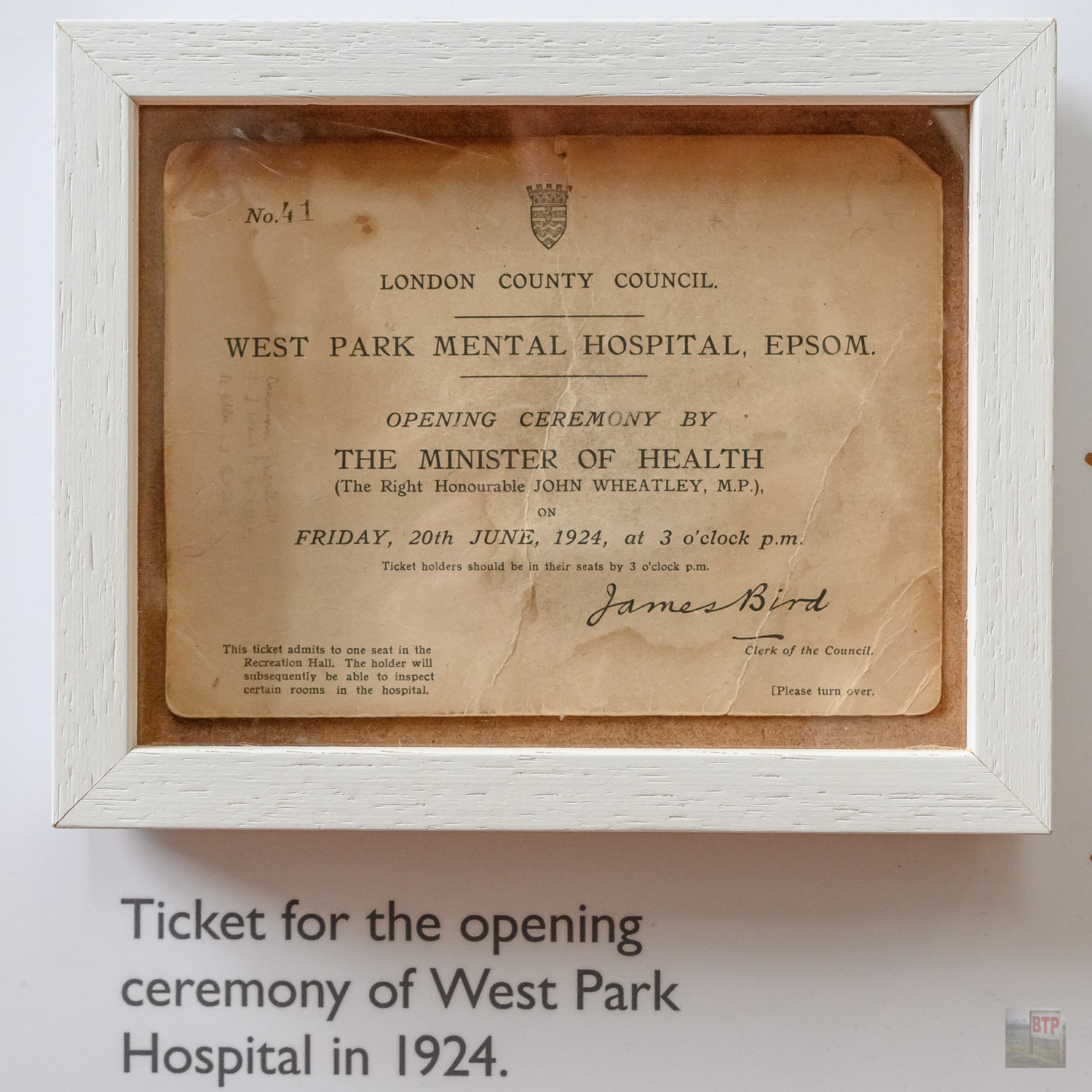

Next is the Horton Hospital chapel, now a cafe and arts venue known as The Horton. They kindly allowed us to photograph the stunningly restored chapel which is now divided into two halves. It also contains some museum displays and artifacts about the Epsom Cluster.

Horton Cemetery

Beyond the Point has worked with Kevin McDonnell of the Friends of Horton Cemetery; a charity formed around the Horton Cemetery Research Project he initiated in 2020. We visited this overgrown cemetery in June 2024 with him to cover this overlooked section of the Epsom Cluster’s land. Thanks to Kevin for providing the following information.

Horton Cemetery was created in 1899 for pauper burials of the unclaimed bodies of patients who died in the eventual Epsom Cluster hospitals. The original cemetery was created for 900 bodies but it was soon realized that this figure would quickly be reached and the cemetery was extended in area in 1903 to about 4.5 acres. By the time the cemetery was closed in 1955 it held about 8,600 bodies. The bodies were left unclaimed by family and friends for a variety of reasons, including poverty; burial elsewhere was not affordable, shame; the family did not want it known that they had a member who had died in an asylum, and rejection; the person who had died had caused disruption or unhappiness or embarrassment, that the person who had died had outlived all their family members and friends, and abandonment or error; the person who had died had been admitted to the hospital by somebody who had left an incorrect contact name and address.

The vast majority of people buried as paupers in the cemetery had an unnamed grave, merely a marker with a grave number. No map has been found of the cemetery so currently it is not possible to find who is buried where. Some people, perhaps 30 to 40, had named grave markers paid for by family or friends but these have been removed and all the grave markers seem to have gone. The burial records show us that there are about 6,600 graves, about 4,800 were used once and about 1,800 were used twice, less than hundred were used three times. Although the cemetery was closed for further burials in 1955 it was always kept in a very neat and tidy condition and great respect for the people buried there continued right up until 1983 when it was sold to a local developer by the NHS. After this point the cemetery was allowed to slowly fall into dereliction. The ground is covered with trees, saplings, shrubbery and ground cover. Today it is almost completely overgrown and in some areas dug up by badgers and foxes, occasionally bringing human bones to the surface. The land has been used to dump builders’ waste, white goods and as a camp by rough sleepers. The ground, once well maintained for so long, is the last resting place of thousands of mental health patients that has become a mark of shame, disrespect and dishonour. An Epsom & Ewell Borough Council Officer has described this cherished land, with almost 9,000 dead mental health patients buried there, as ‘amenity woodland’, presumably to imply that there is a base financial value to this priceless ground which is likely the largest mental health cemetery in the UK and perhaps in Europe. A place that should be held in the highest regard, honoured and maintained as a memorial to the lost and abandoned mental health thousands buried there, lies defiled and desecrated. Horton Cemetery is one of approximately 140 such cemeteries in the UK, largely completely forgotten when the NHS sold the former asylums and their estates around the millennium.

The good news is that a local group, helped by many volunteer genealogical researchers from all over the UK and even overseas is fighting back. The Horton Cemetery Research Project is the engine room behind The Friends of Horton Cemetery charity (Reg. No. 1190518). They are slowly bringing the people buried in the cemetery ‘back to life’ by researching, writing and publishing their stories. You can read approaching 500 of their stories published so far here https://hortoncemetery.org/the-people/horton-cemetery-stories/. If you support what they are doing, would like to know more, hear about a similar cemetery near you or would like to become a volunteer genealogical researcher you can contact them at https://hortoncemetery.org/contact/. The charity wants to prevent the cemetery land’s current owner from developing it by deploying a Compulsory Purchase order or similar, and turn it into a long-overdue memorial garden; to finally give the thousands of mental health patients buried there the respect they deserve since the sale of the cemetery in 1983.

Long Grove Hospital

Long Grove Asylum was built from 1903 and opened in 1907. It was designed by famous asylum architect George Thomas Hine; pioneer of the late-Victorian compact arrow plan. It was almost a replica of Horton Asylum with some slight changes allegedly influenced by the American Kirkbride plan, with more heavily zig-zagged interconnected wards. Its admin block and red brick construction, rather than Horton’s unusual pale brick, were otherwise its main differences. Its corridors were walkways open to the outdoors, unusual for compact arrow asylums, although were curved in shape like Horton. Eventually it became Long Grove Hospital as the asylum tag was dropped in accordance to the changing times. It famously had Ronnie Cray as a patient, admitted in 1958. The hospital closed in 1992, laying derelict for a while until demolition and residential reconstruction by the early 2000s shortly prior to the emergence of the online urban exploration scene and thus escaping significant photographic record.

The stunning three-storey administration block at Long Grove. This and two interconnected sets of wards on either side survive as residential conversions. Otherwise, the enormous hospital has been demolished. (Aerial photograph from RightMove)

St. Ebba’s Colony

This hospital was the third to be built and was designed by William C. Clifford-Smith who worked on the Manor Hospital. It opened in 1904 as Ewell Epileptic Colony, being more specialised than the other asylums of the cluster as efforts to separate epileptics from the mentally ill emerged at the start of the century and provide them with their own institutions. It was built in a colony layout of separate villas to provide a more domestic ‘village’ feel. This plan was internationally popular for mental hospitals, but English asylums were slow to adopt it, with the later West Park being one of the few nationally to only bear aspects of this plan. This means that St. Ebba’s was different from both the other hospitals at Epsom, and from those across the country, both in its form and its function. After use as a Great War hospital, in 1927 it was changed to Ewell Mental Hospital, taking on a more conventional role like the other asylums. However, in 1962 it changed to an institution for the mentally subnormal, like The Manor Hospital, rather than mentally ill. From 1995, parts of the hospital closed for ongoing residential redevelopment, with the water tower being converted but recreation hall, services and kitchens being demolished. However, many villas still remain in use by the NHS today.

Above: The administration building at St. Ebba’s. The recreation hall and services once adjoined to its rear have since been demolished.

Below: The various villa-style detached ward blocks of the hospital, still used by the NHS. Also pictured is the iconic water tower and boiler house, now residential conversions.

The grounds of St. Ebba’s, along a footpath affront the modern MyTime/Oasis Therapy Suite building, contains several memorial stones to former patients of the hospital. Kevin McDonnell cleared these overgrown stones in June 2018. The top two dates are birth and death year and the bottom line, e.g. “Here 32 years” says how long they were in St. Ebba’s for. We cannot assume that the people died in St. Ebba’s but if we do assume that, for example Pierre Charles Menguy – 1942 – 2011, lived for 69 years and was there for 64 years. He must have been admitted when he was 5 years old. A sobering realization.

West Park Hospital

West Park is perhaps the most infamous of the Epsom Cluster hospitals and the last built in 1924. It is also perhaps the externally best surviving and most sympathetic residential conversion, which kept a great deal of the ward buildings and restored their facades to their original glory. The mental hospital represented a unique modern approach separating wards into individual villas, largely connected with outdoor corridors. West Park was never officially termed an asylum, instead opening as West Park Mental Hospital, which was becoming increasingly common in an attempt to distance these more modern institutions from the asylums of the Victorian era. However, the expansive institution was an asylum in all but name. Like many asylums, its opening was delayed by WWI and used as a Canadian war hospital, having been largely complete since 1917 and in planning since 1906. The hospital catered for over 2,000 patients. The hospital became partially disused over the 1990s until full closure in 2003.

The administration building at West Park was stylish yet streamlined. Classical, yet not overindulgent like its Victorian counterparts. Another understated touch was the four false pillars protruding from the brick facade. It in-keeps with the look of the hospital’s wards, maintaining a level between the patients and the staff, quite unlike the more imposing facades of earlier mental hospitals.

The water tower at West Park was, like the admin block, also more domestic in appearance, complete with slate roof. Like most asylums, water towers became landmarks and this one has fortunately been preserved. West Park was designed by the original The Manor and St. Ebba’s architect William C. Clifford Smith like the rest of the hospital, and constructed from 1913-21. It would appear to be the only building of the hospital that is listed, although the remaining parts of the five hospitals at Epsom form conservation areas.

The wards at West Park were set out as separate buildings connected by outdoor walkways and underground service tunnels. This was a more modern approach moving towards the colony plan seen at St. Ebba’s, seen as more domestic and resembling a village community, with detached buildings. England was slow to adopt this international trend due to asylum boards being set upon properness and tradition. West Park was a compromise, somewhere between a colony plan and the compact arrow plan of Long Grove and Horton with wards arranged in an echelon, but with blocks of a more standalone design and the connecting corridors being outdoor and more immersed in the hospital grounds.

Most asylums were given airing shelters; sun and weather shelters placed within the grounds of the asylum. Green space was recognized for its benefit to mental health in the Victorian Era, and this formed a key part of asylum design, with each ward equipped with an outdoor space called an airing court. The airing shelters at west park take on both a circular and rectangular plan and have been preserved and restored.

The only remaining derelict building of West Park Hospital is Scott House, situated north-west behind the main building. It served as the male section of a phthisis (tuberculosis) and dysentery hospital; two common diseases in the early twentieth century that the mental hospital needed the facilities to deal with if its patients got sick.

The following photographs were taken of the interior of Scott House in December 2024 and show how much it has deteriorated internally since it was disused over the past decade. It appears that many of its furnishings, including skirting, some windows and doors were ripped out to facilitate the removal of some of the medical equipment left inside, although some still remains. Despite this, it still echoes the character of the wider hospital during its abandonment. The west wing of the house had suffered from heavy stripping, yet still featured much of this unwanted material piled up in one of the rooms.

The central area of Scott House had suffered fire damage after an arson attack in the early 2020s on the northern rear of the building. Opposite this area is the main entrance, with corridor going off west.

The smaller eastern end of the house was perhaps the most photogenic in the midday winter’s sunlight, with extensive paint peel and some nice pastel colours for the sake of photography. It may represent only a tiny fraction of West Park, but like most of the great asylum buildings it one day will cease to exist in its intended medical state.

One of the few buildings at West Park still used by the NHS is Ramsay House at the south of the site opposite admin. This was originally the admissions hospital for West Park, where patients would first be received before determining their future at the hospital and which ward to send them to. It is an impressive building in itself, despite being only a small part of the complex.

At the north end of the site beyond Scott House are three more buildings still used by the NHS. These villas comprised the two-storey Farmside in the centre, flanked by two single-storey villas Woodside and Burnham to the east and west. Farmside was a day hospital and became a nursing college, whilst Woodside became an adolescent unit.

Hollywood Lodge

Originally Horton Lodge, this was an old manor that predates the Epsom Cluster hospitals. A house existed on its site since at least 1778. It formed the residence of the Horton Estate, part of which was purchased by LCC for the asylums. It was partially remodeled in the early-mid nineteenth century, although it is not clear to what extent the surviving building’s construction is original and altered and when. Its residents continued to live in the lodge until 1927/8, when it was sold to the Manor Hospital. It was then used as a small annexe for The Manor and allegedly West Park Hospital.

Sources

https://www.thetimechamber.co.uk

https://www.countyasylums.co.uk/

https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk

https://eehe.org.uk/25027/hospitalcluster/

https://thehortonepsom.org/heritage/

https://hortoncemetery.org/the-cemetery/the-epsom-cluster

With thanks to Kevin McDonnell and Nick Combes

This entry was posted in Location Report