In 2015, Beyond the Point was given exclusive access to film and photograph inside the derelict site, with filming requests from the likes of the Discovery Channel declined. This was done with the intention of creating a feature film entitled ‘Secrets of Severalls’, although it never came to fruition due to time constraints and the mammoth scope of the project. However, we have recently revived the footage and are in the process of making a new feature film. As of 2024, this is a work in progress, but it’ll be worth the wait. The video below provides a glimpse at the footage we recorded, and the images in this article (unless otherwise stated) are from our 2015 visits, with remastering work applied to bring the pictures back to life more inline with our current standards.

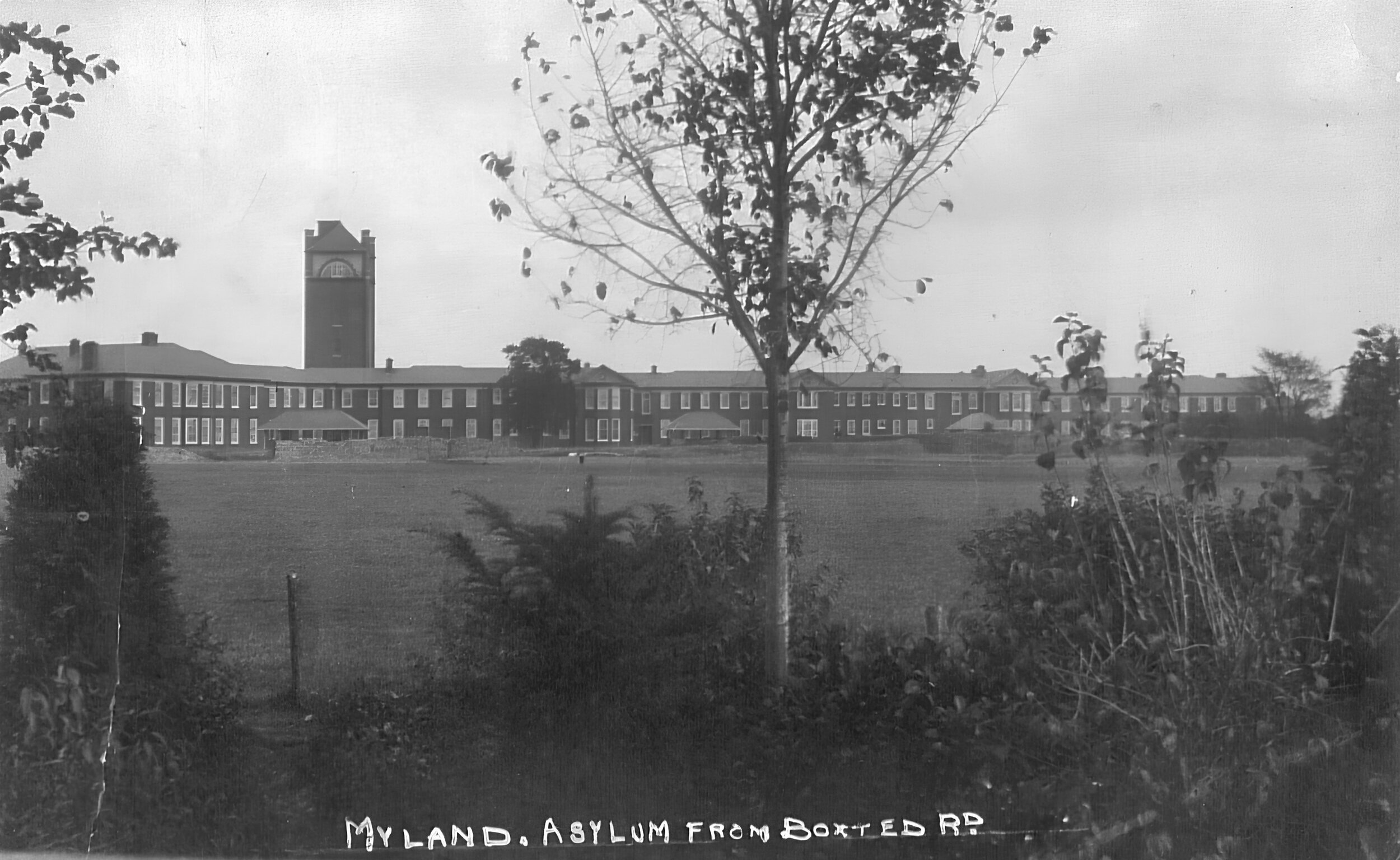

In 1851, the first Essex County Lunatic Asylum, as they were known, was built in Warley. As the demand for such buildings was on the rise it was decided to build a second asylum away from Brentwood, and planning started in 1902 when the Severalls site in Colchester was chosen.

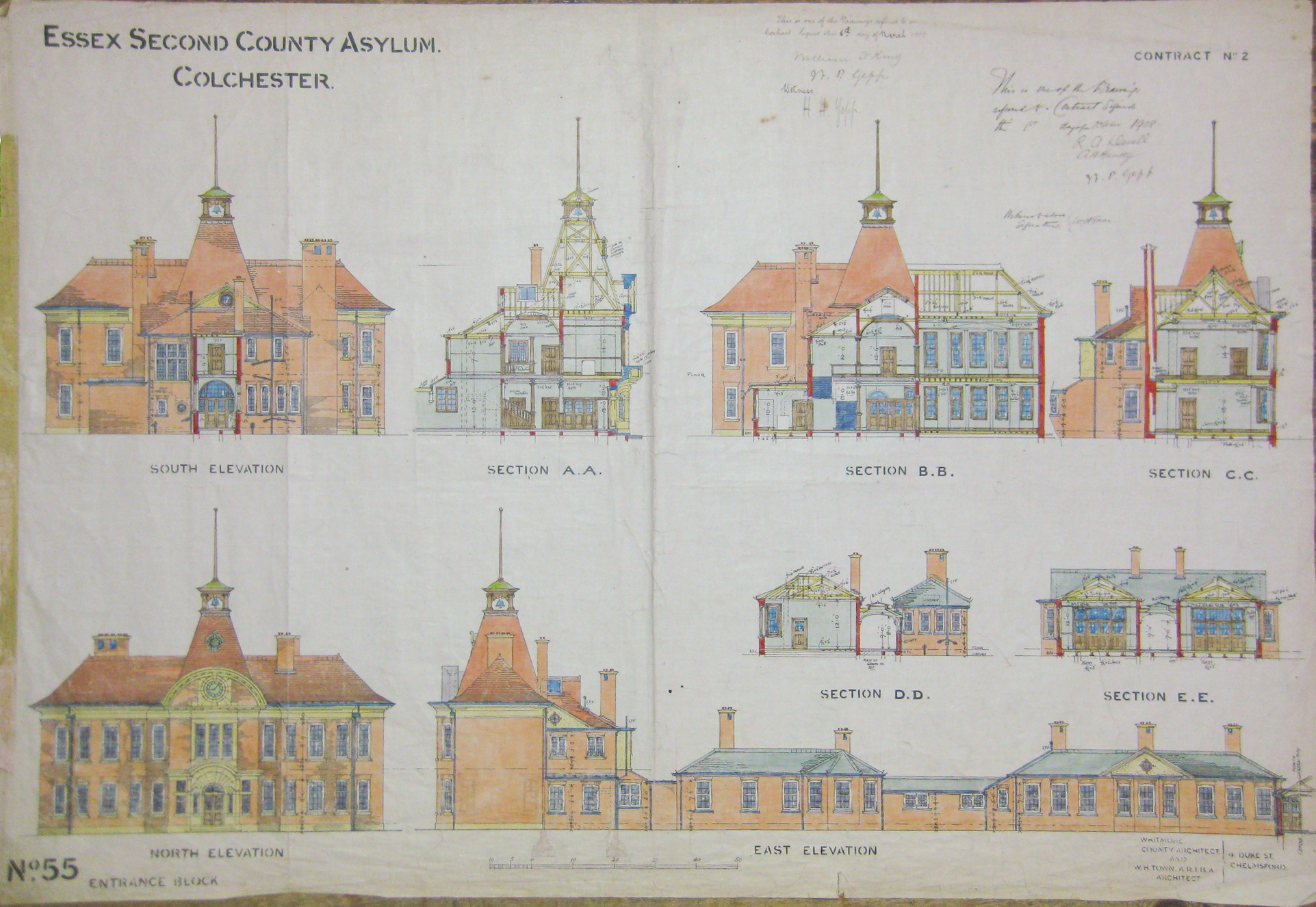

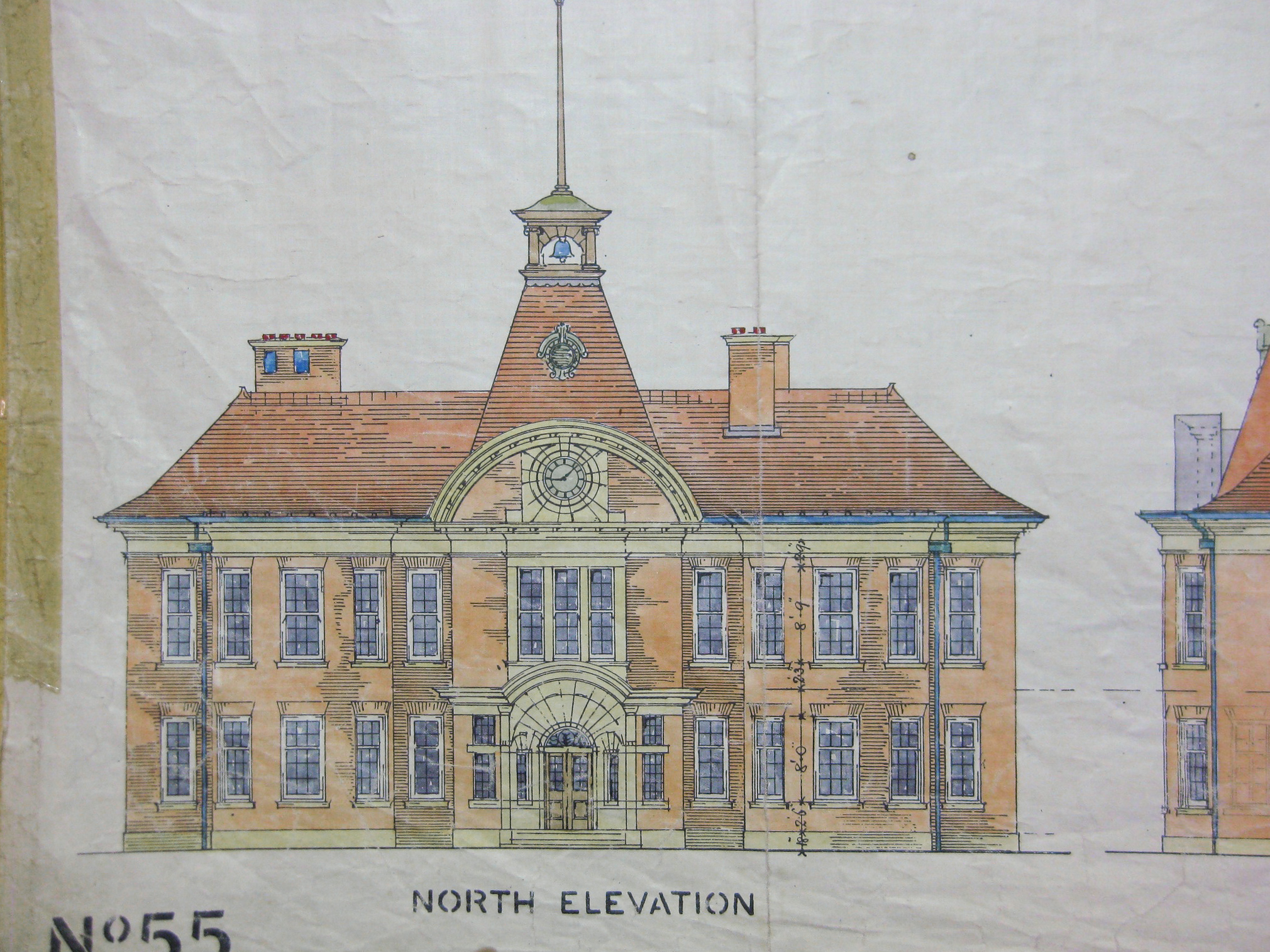

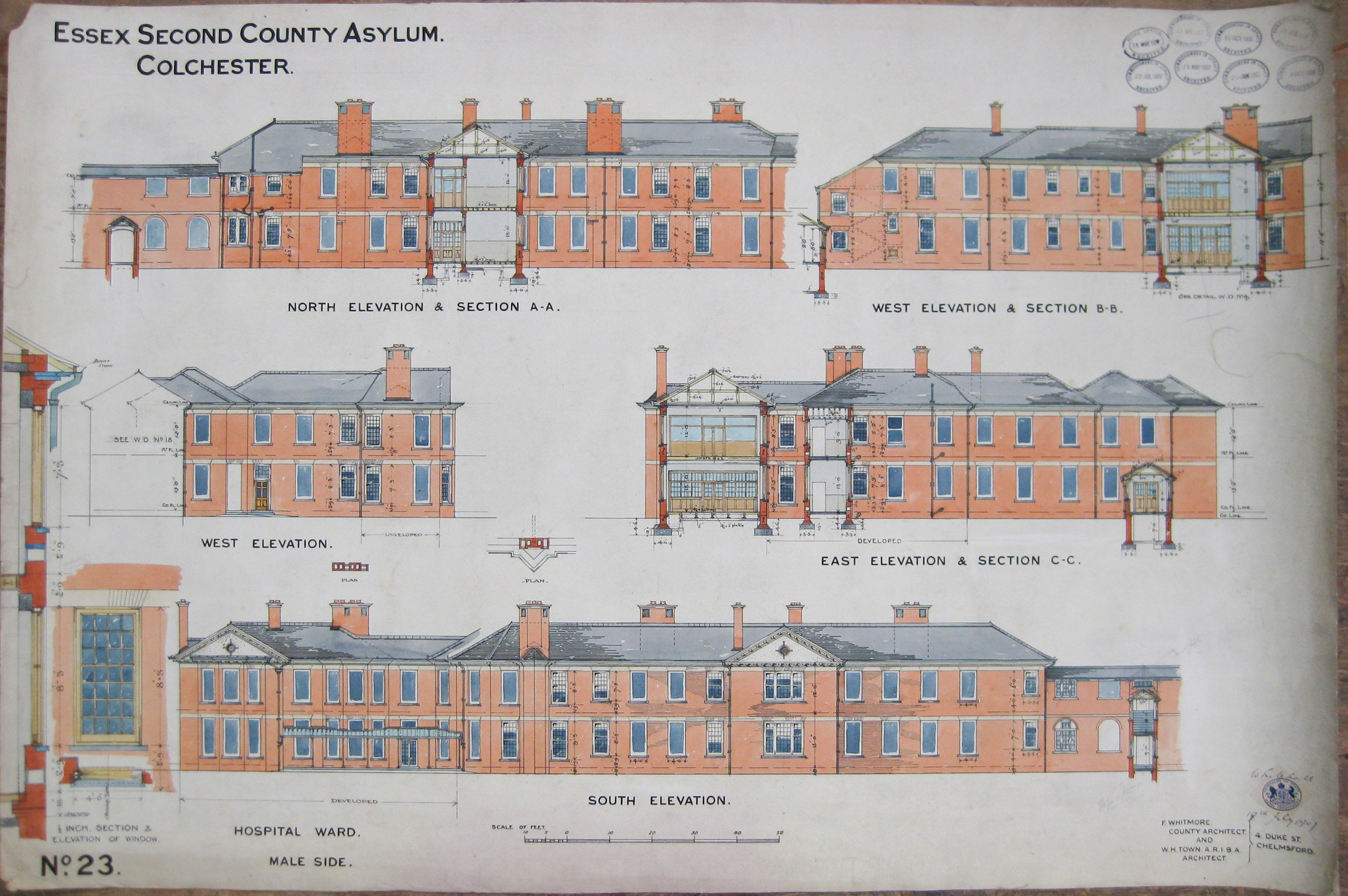

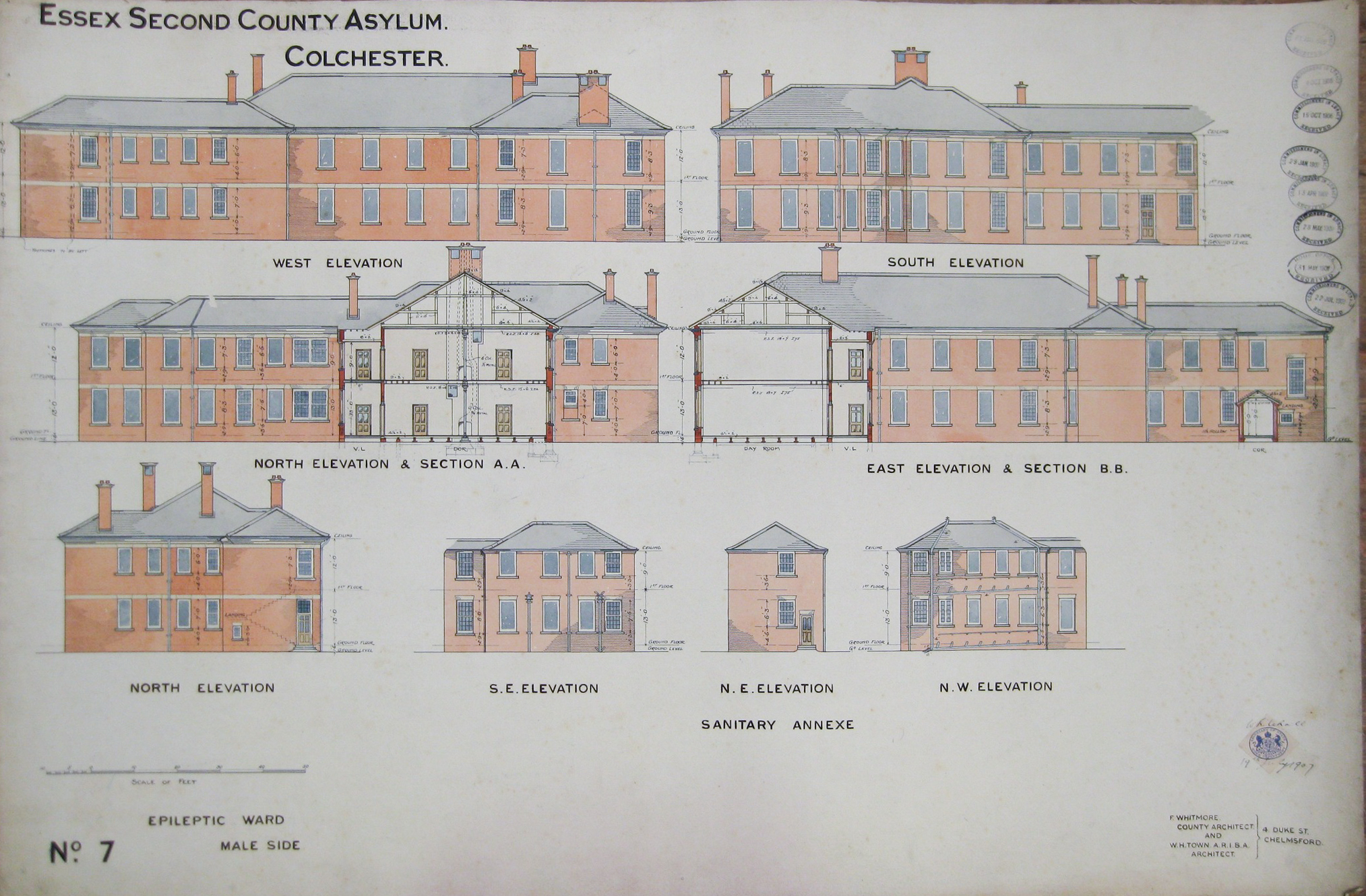

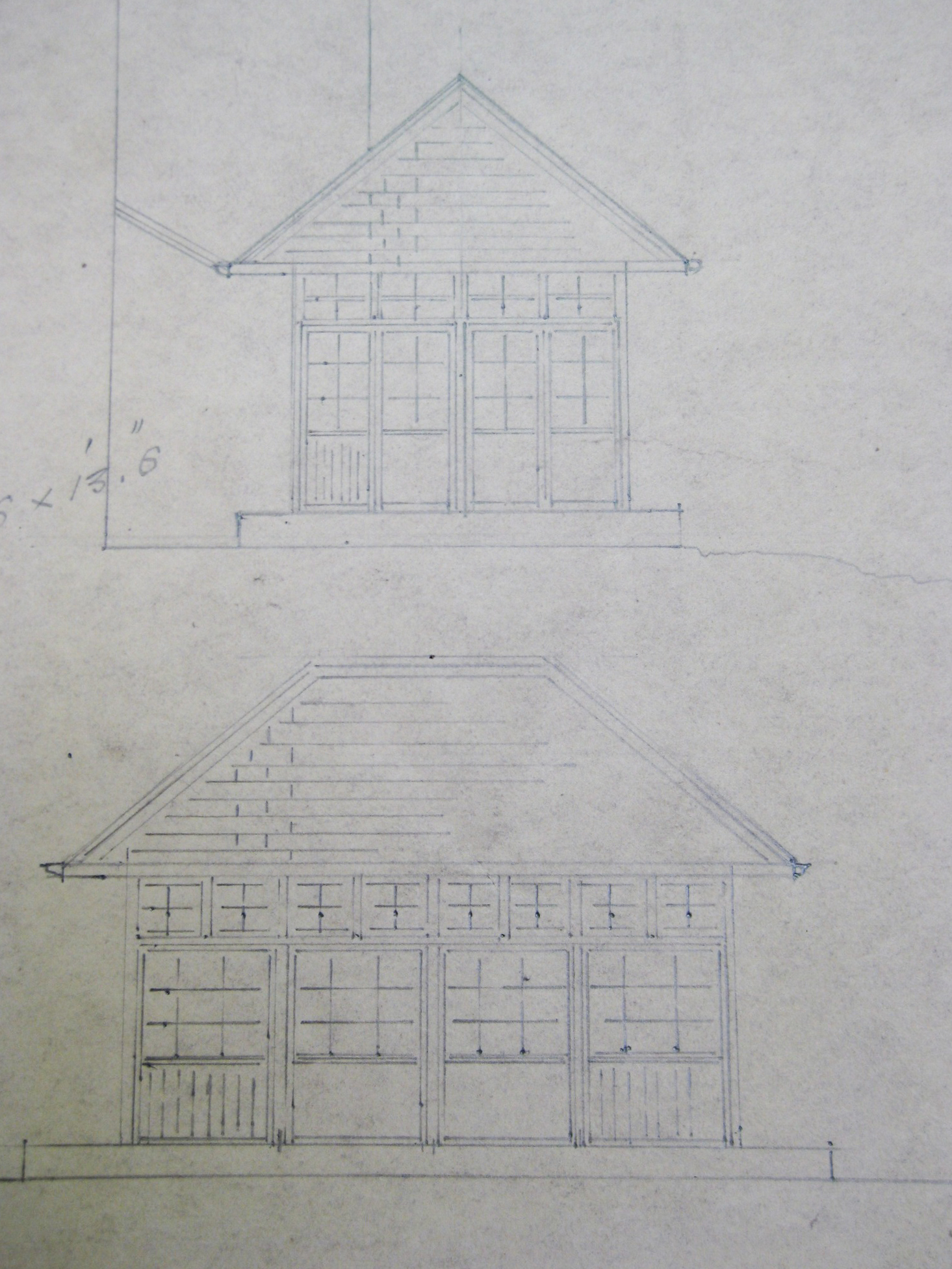

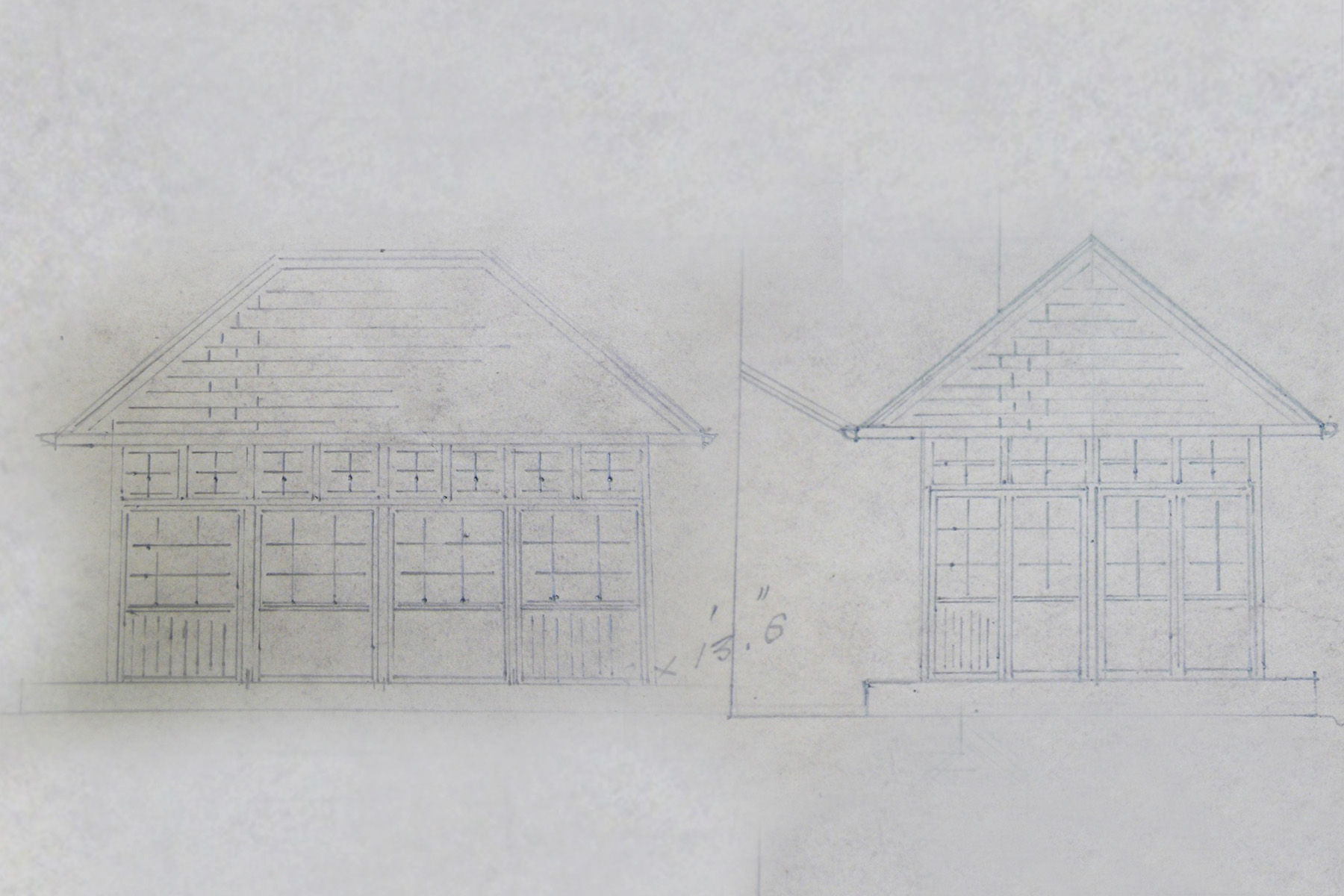

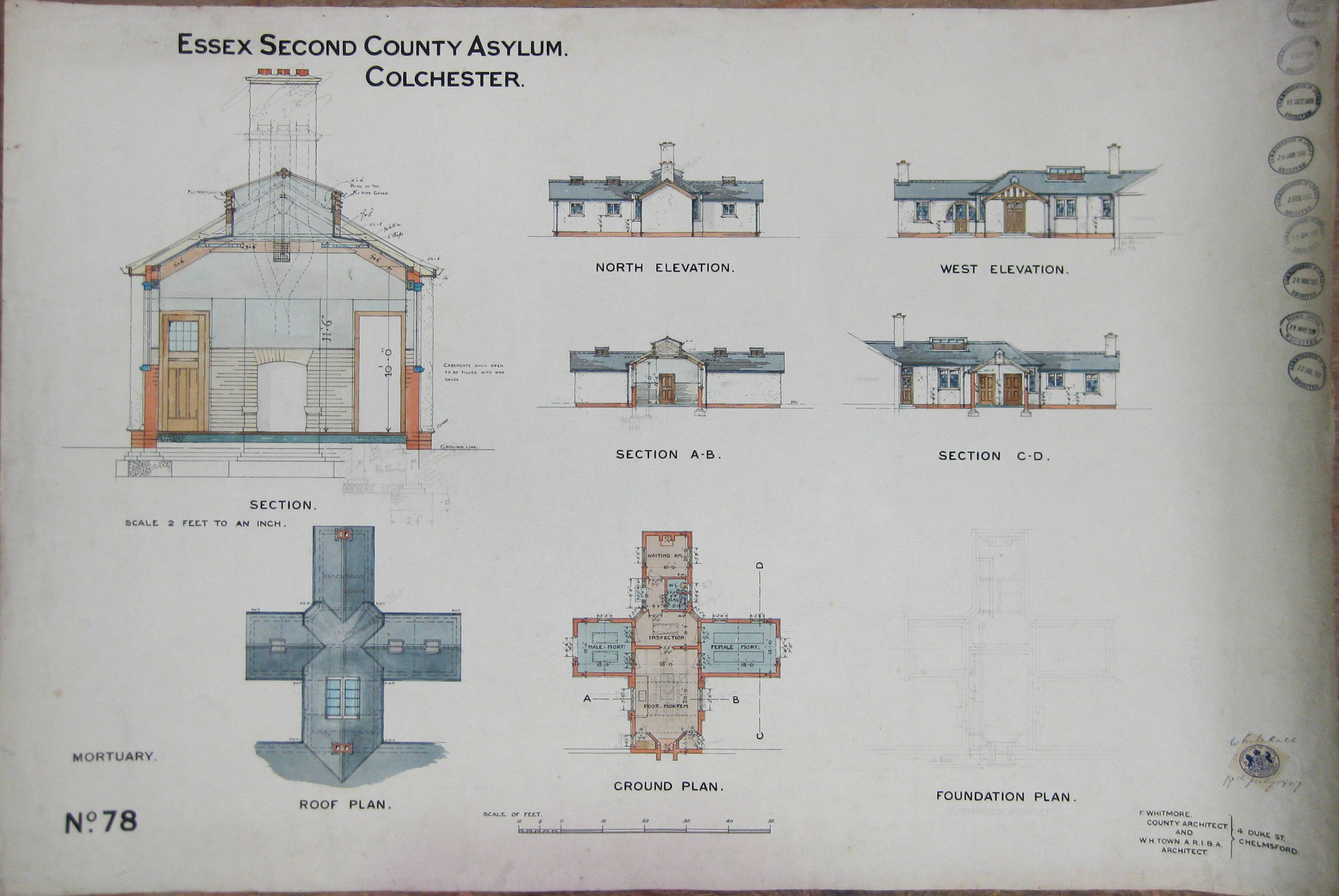

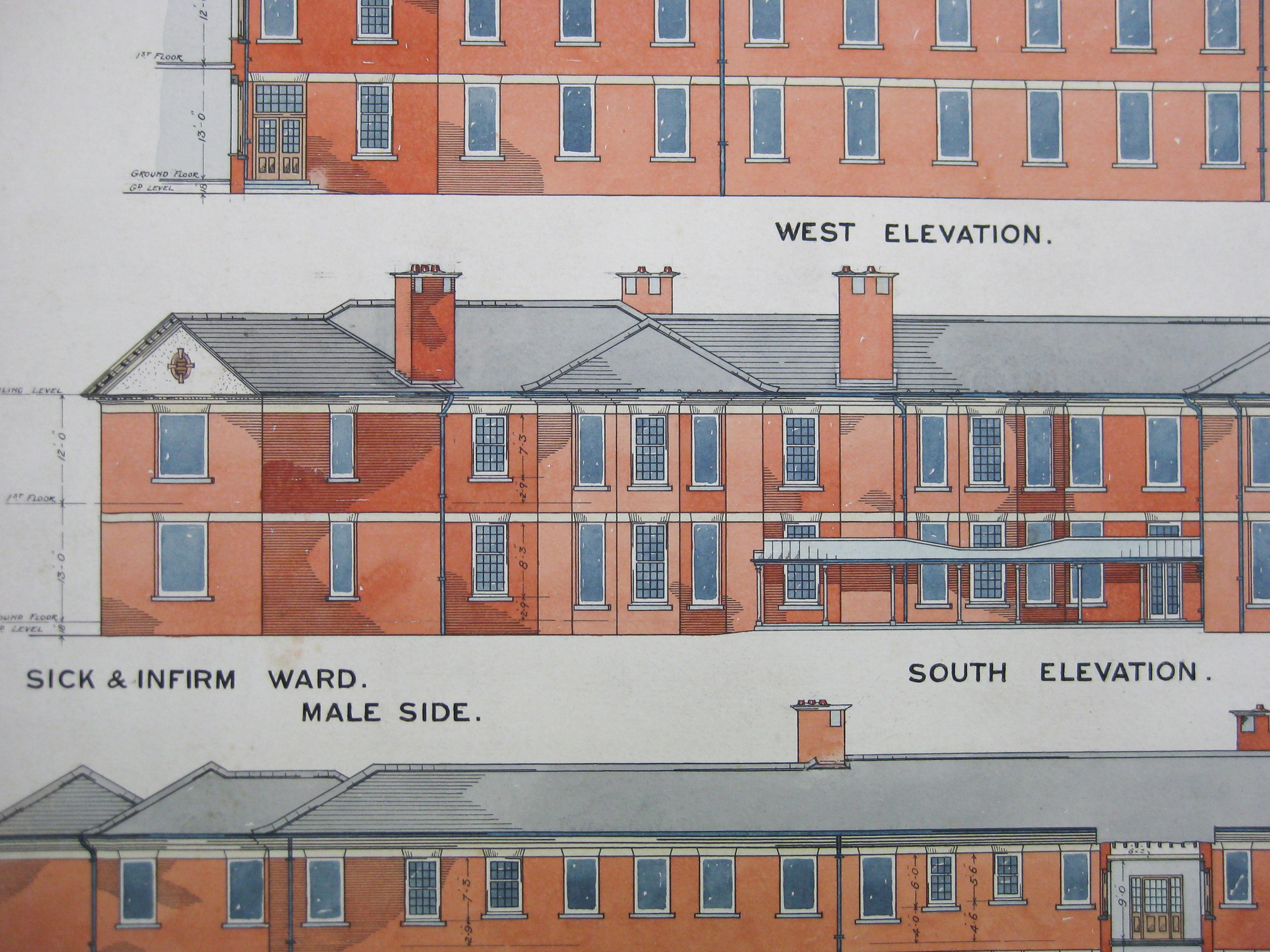

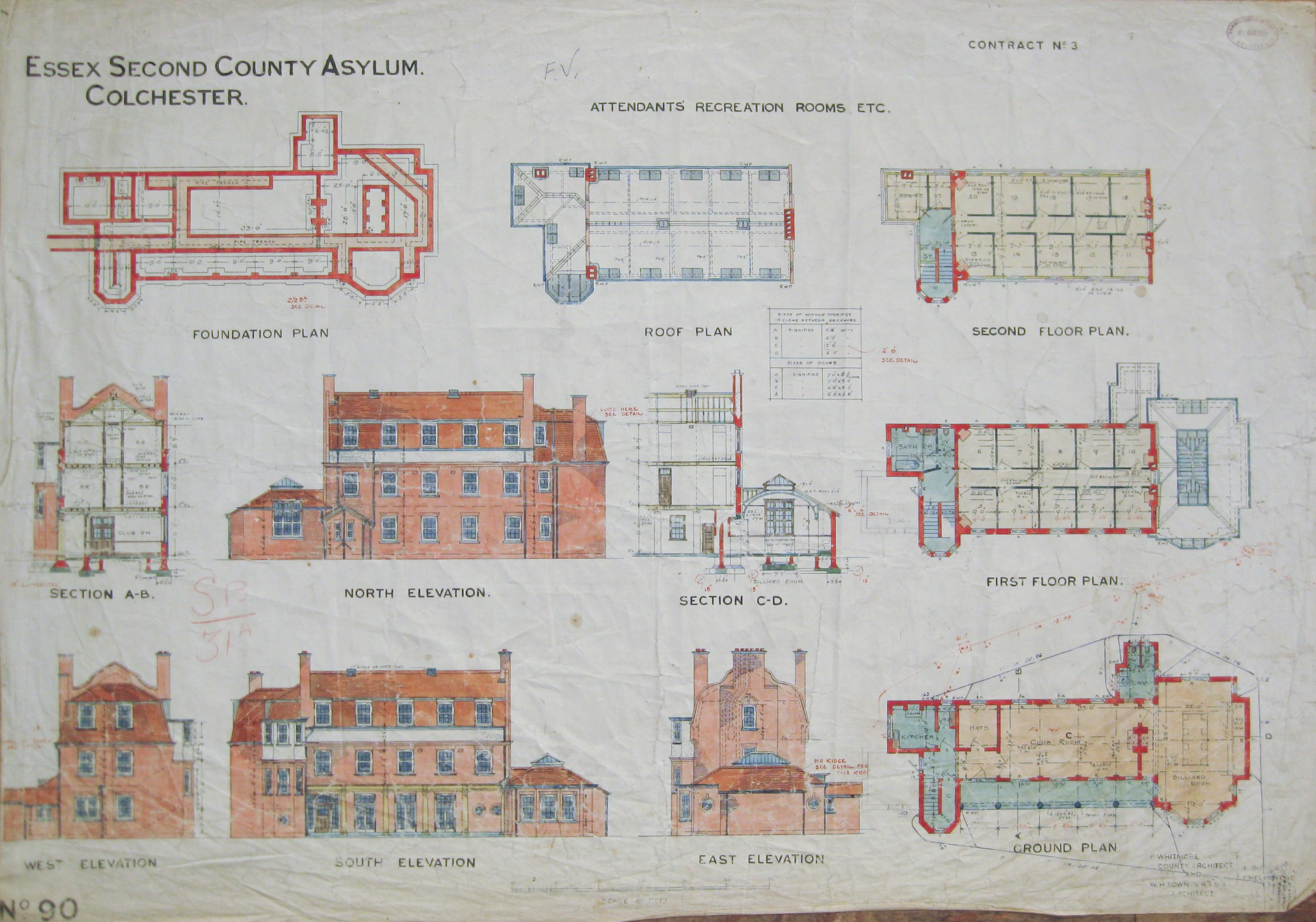

Local architects Frank Whitmore and William H. Town of Colchester were selected and designed the hospital based on the echelon variant of the compact arrow plan, where the whole hospital was accessible by long corridors – some of them being hundreds of feet long. These corridors connecting the wards arranged along the edges in a chevron shape, with central services in the centre. Cottages were built for gardening and engineering staff and detached accommodation was also provided for senior medial staff such as the medical superintendent. Severalls also saw the addition of various villas in its grounds, often for private patients.

The foundation stone was laid on 21st June 1910 and the first 50 patients were admitted in May 1913. Like many of the asylums built the hospital had its own water and electricity supply as well as a farm for the patients to work on. A year after opening the First World War started, and it was requisitioned by the military for use briefly as a camp and then as a military hospital. In the early 1930s, the hospital went through a period of further change, with additional villas and nurses’ blocks being added, as well as its name being changed to Essex and Colchester Mental Hospital. During the Second World War, on the 11th August 1942, the hospital was bombed allegedly after being mistaken as a factory, killing 38 patients and injuring 23, all of whom are buried in graves in Colchester Cemetery. There is a memorial to the victims outside the admin block today.

As its peak Severalls was a giant site and could accommodate 2,000 patients – in comparison to the new Colchester General Hospital was around 763 beds. Like many asylums, Severalls joined the NHS in 1948 and entered a period of gradual demise post-WW2, with governmental pressure and shortcomings in practices becoming more entrenched. Controversial therapies such as electroconvulsive therapy and prefrontal lobotomies were all carried out here during this period, and drugs were becoming more readily available. Diana Gittins’ Madness in its Place; the definitive study of Severalls, paints a grisly picture. A certain Dr. Sherwood was brought in during the 1950s to perform the experimental new lobotomies, and was eventually dismissed by the superintendent for his questionable practises. The following paraphrased account is particularly striking and presents a grim picture of the hospital:

A patient voluntarily admitted himself in 1953, suffering from depression and paranoia. His time at the hospital initially lifted his spirits, until he was readmitted for being paranoid his neighbour had it in for him (which neighbours often do). He was given the brutal treatments of insulin shock therapy and ECT. He was discharged before returning again due to the neighbour. For another year, he underwent no fewer than sixteen ECT treatments, leaving him ‘tense and agitated’. It was then proposed he underwent a lobotomy. He was next reported to have suffered from headaches and depression, trying to commit suicide several times after being administered drugs. He was given a lobotomy. Days later, he had a fever and was sick, eventually losing the ability to feed himself and with a weakened pulse. By the end of this rapid decline, he could barely respond to stimuli. Dr. Sherwood decided to explore his brain with a needle in 1956, after which he suffered severe neck pain and fever. Ten days later, he was dead.

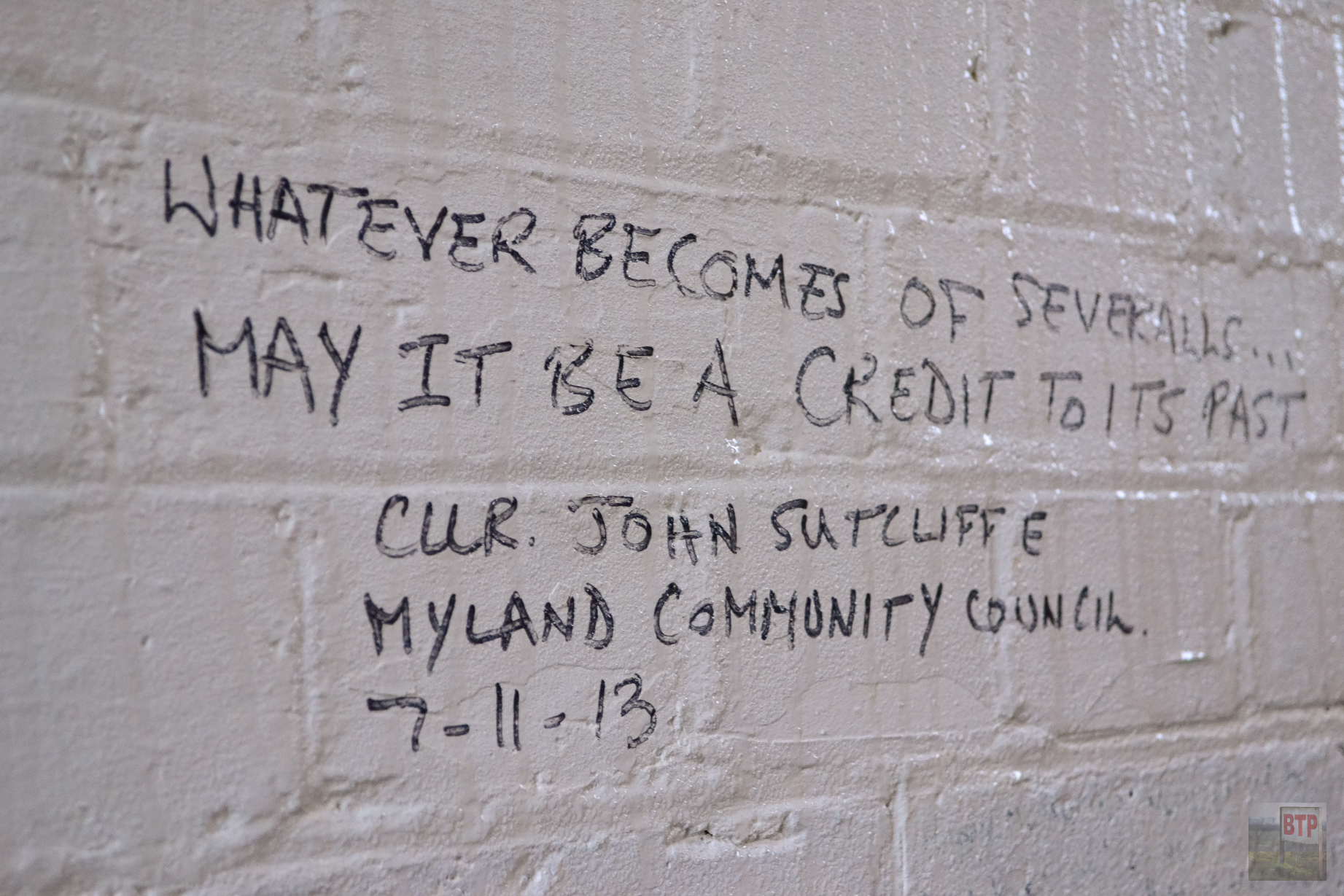

As the hospital population started to decrease due to community care initiatives, wards gradually closed throughout the 1990s and Severalls shut its doors for good in 1997. In the years that followed, the derelict asylum became synonymous with urban explorers until the 120 acre site was sold in 2016 with the majority of it demolished to make way for 1,250 homes. Housing began to be complete with people gradually moving in over 2017 onwards, with ultimately only the western male wards, admin block, water tower, Larch House and airing shelters escaping demolition. The recreation hall burnt down around 2005 due to arson, although the other obvious choice of buildings worth saving was the stunning chapel. However, this was also demolished, said to be due to structural issues. The conversions have been done well, providing an accurate impression of what the buildings would have looked like in their heyday, although the overall impression is one of disappointment given that such small parts of a huge site were saved.

Access Road

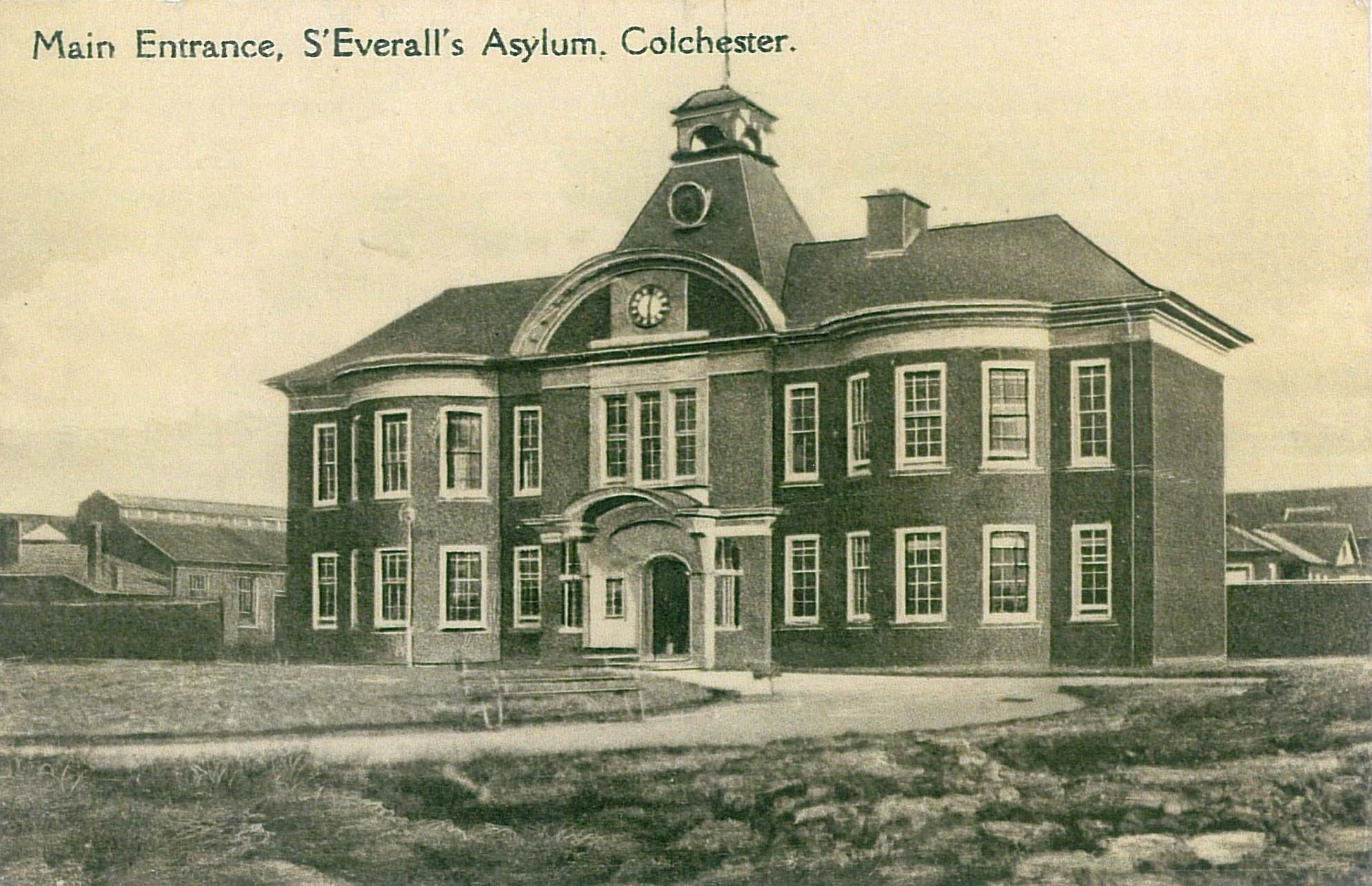

Administration Building

The admin block would have formed the centerpiece of the hospital. Similar to the rest of the hospital’s design, it was fairly simple and undecorated, yet has a certain elegance. It’s interesting comparing the burnt-out boarded up shell back in 2015 to what it is today. This building has certainly been restored to its former glory.

Corridors

Courtyards & Carriageway

The north side would have been the working end of the asylum which kept it running on a day to day basis, away from most of the wards. The yards in the north-west were industrial in nature, bringing goods in and out via the coachway and lobby and also containing the water tower and boilerhouse. The east side was for laundry etc, roughly in-keeping with the gendered halves of the complex. This area contains a multitude of outbuildings and facilities of which we only photographed a few.

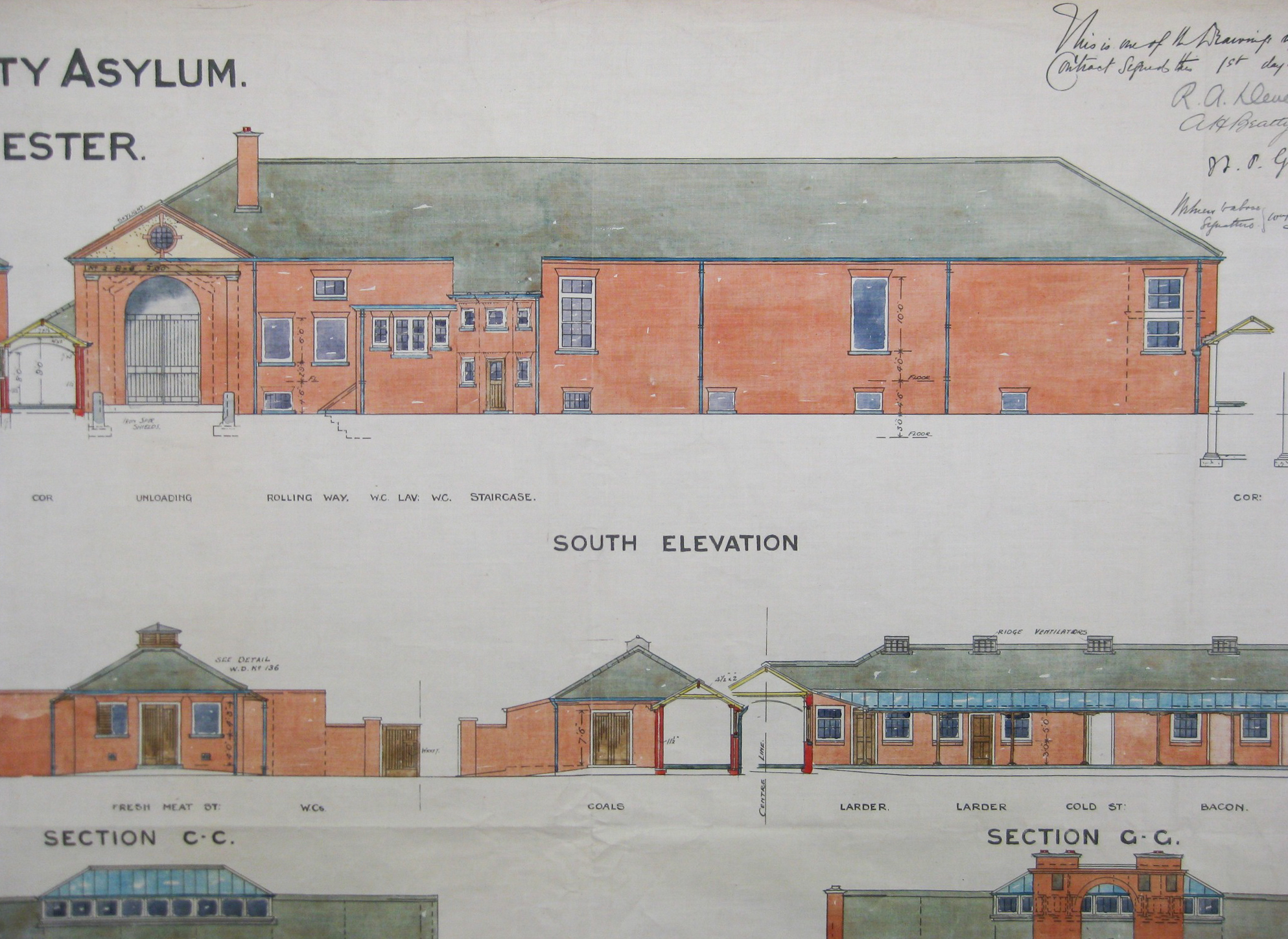

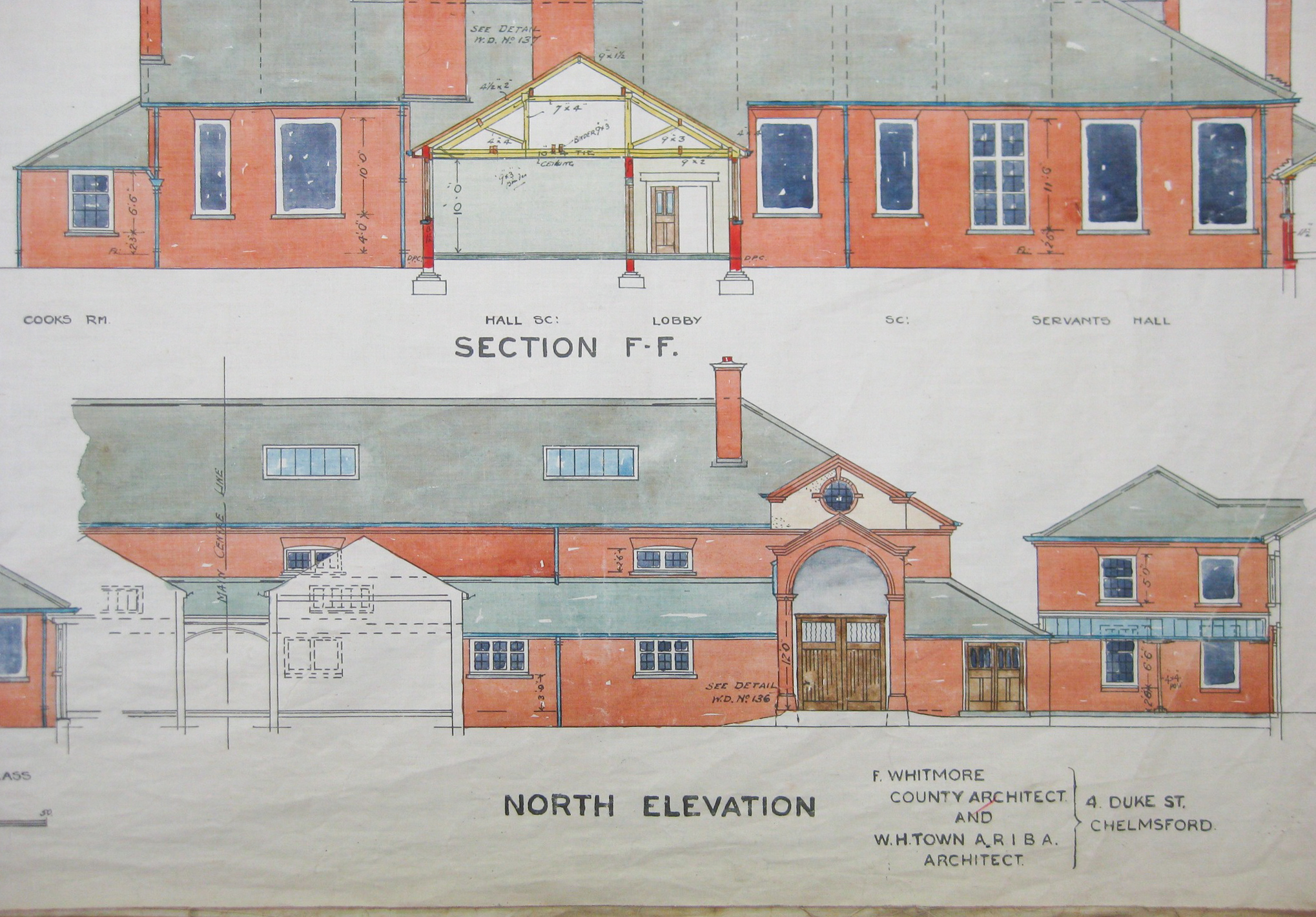

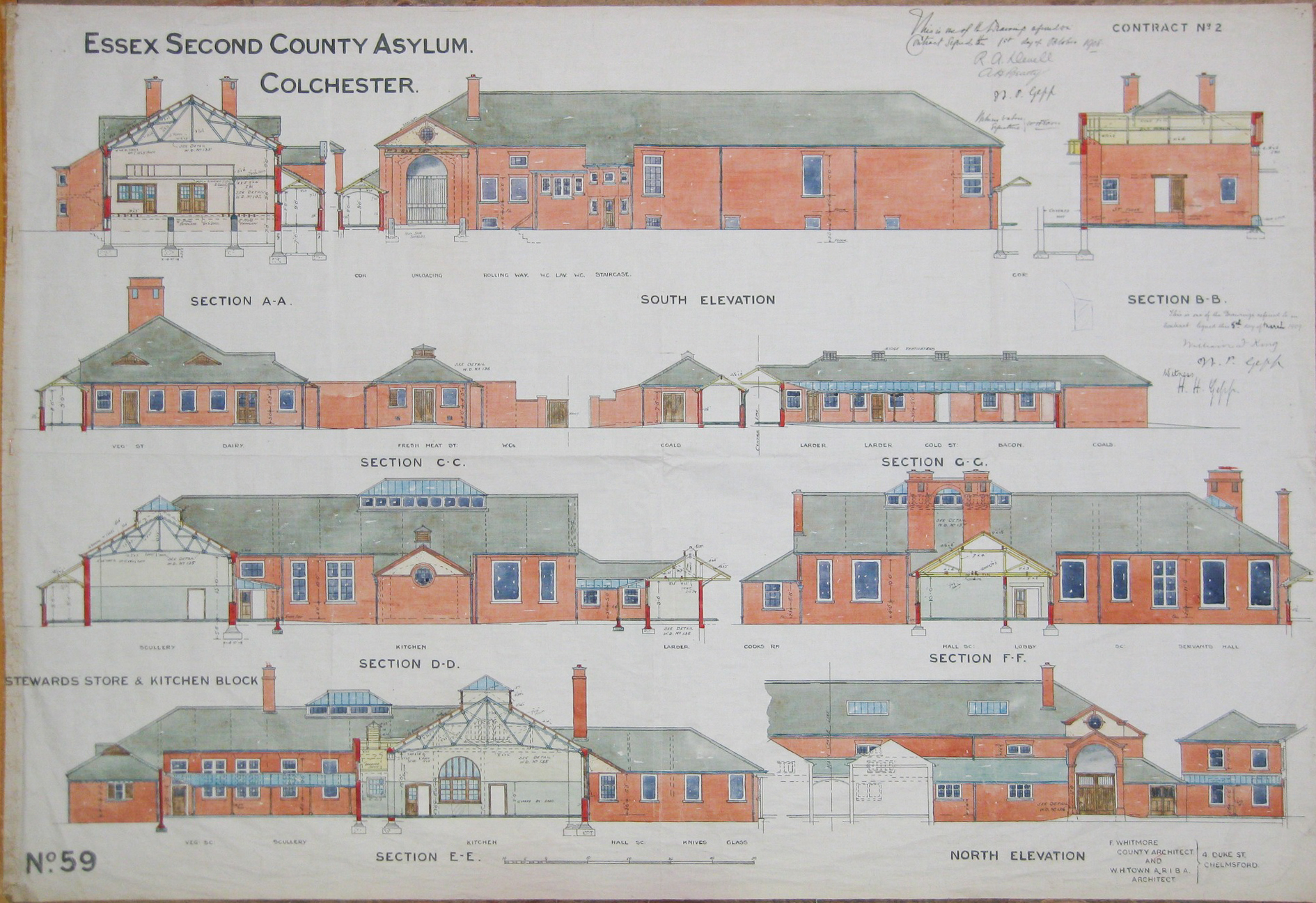

Kitchens

The kitchen was situated in the centre of the site between the admin block and the hall. It consisted of a main kitchen room, with another smaller glazed room off to the size. At the time of visiting, several of the connecting rooms contained large fridges and ovens too. The kitchen itself is still recognizable in various old photos and changed very little.

Stores

Located on the eastern side of the carriage arch, this is where goods would have arrived at the hospital presumably from the carriageway. It was in poor condition, with internal walls added and heavy vandalism, but its mezzanine level and a pulley still survived.

Airing Shelters

These were placed out in the airing courts which served each ward, around the outside of the asylum as well as a few within its inner courts. The county asylum blueprint was heavily based around the benefit of the outdoors and fresh air upon mental health. The airing shelters survived well at Severalls and were restored by a bus shelter company for the modern housing development.

Wards – Exterior

The male wards were in the western half of the building, and the female wards were in the east. Most of these photographs are of the male side, which was partially retained for the residential conversion.

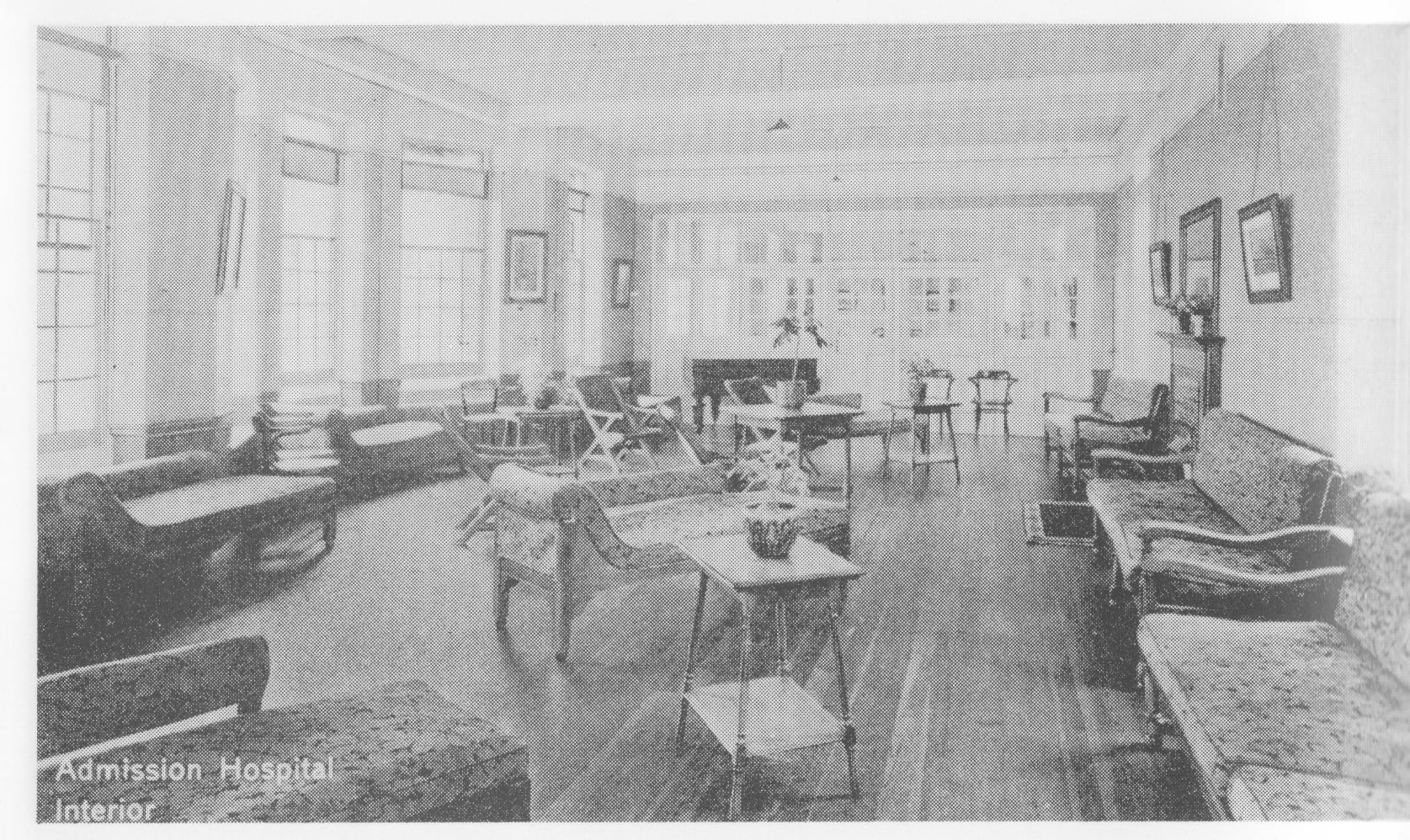

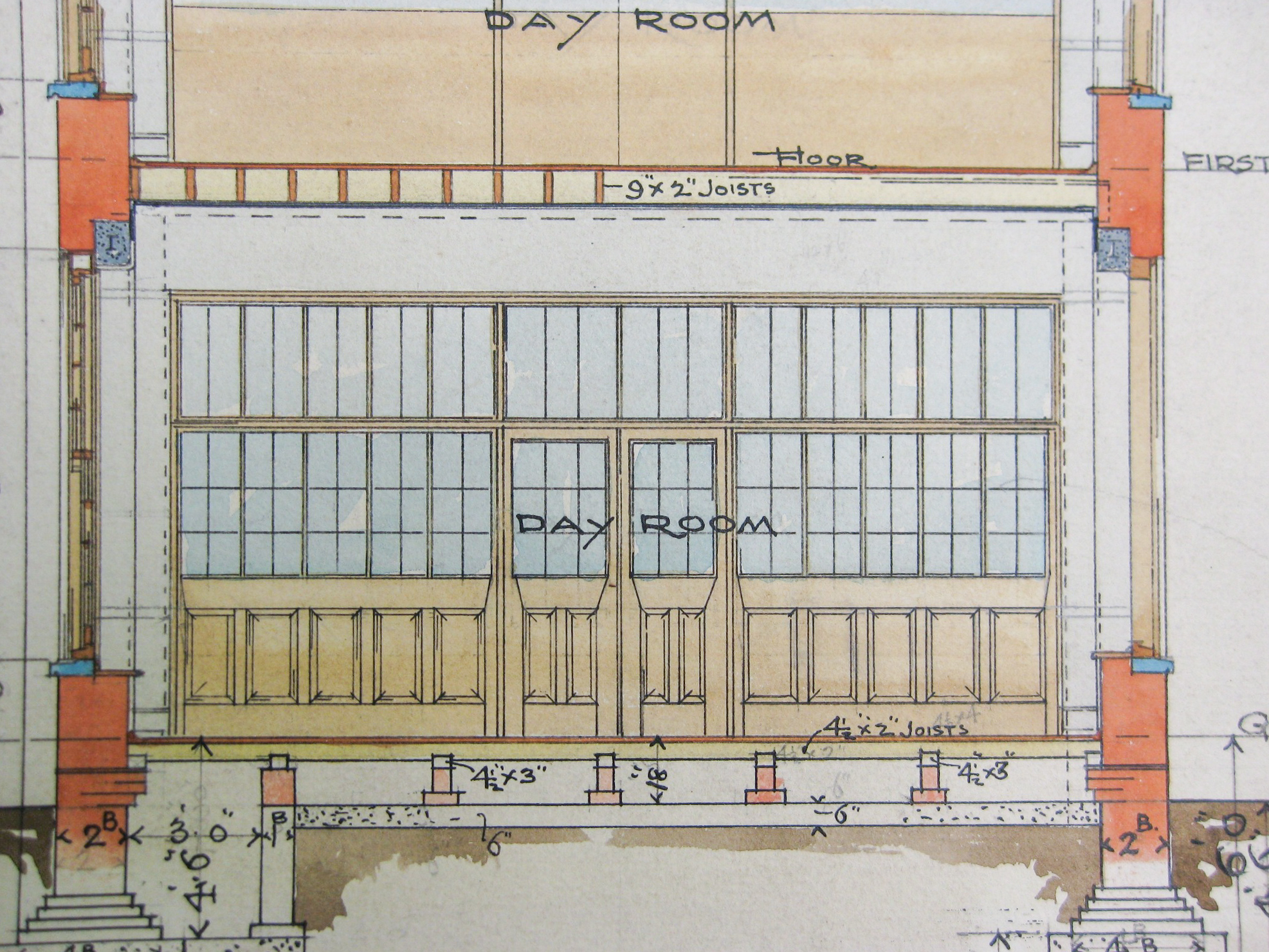

Wards – Dayrooms & Dormitories

This is where the patients spent most of their time. Essentially these two kinds of rooms were communal bedrooms and lounges. The dayrooms are the ones generally with bay windows, sometimes divided with a separate dining room and living room. Severalls had very large ones I believe, maybe a result of its more modern and less-cramped design. The dormitories differed from the dayrooms as they were the linear rectangular rooms with beds and windows along the sides and a walkway down the centre, much like a normal hospital, although we didn’t photograph as many of these.

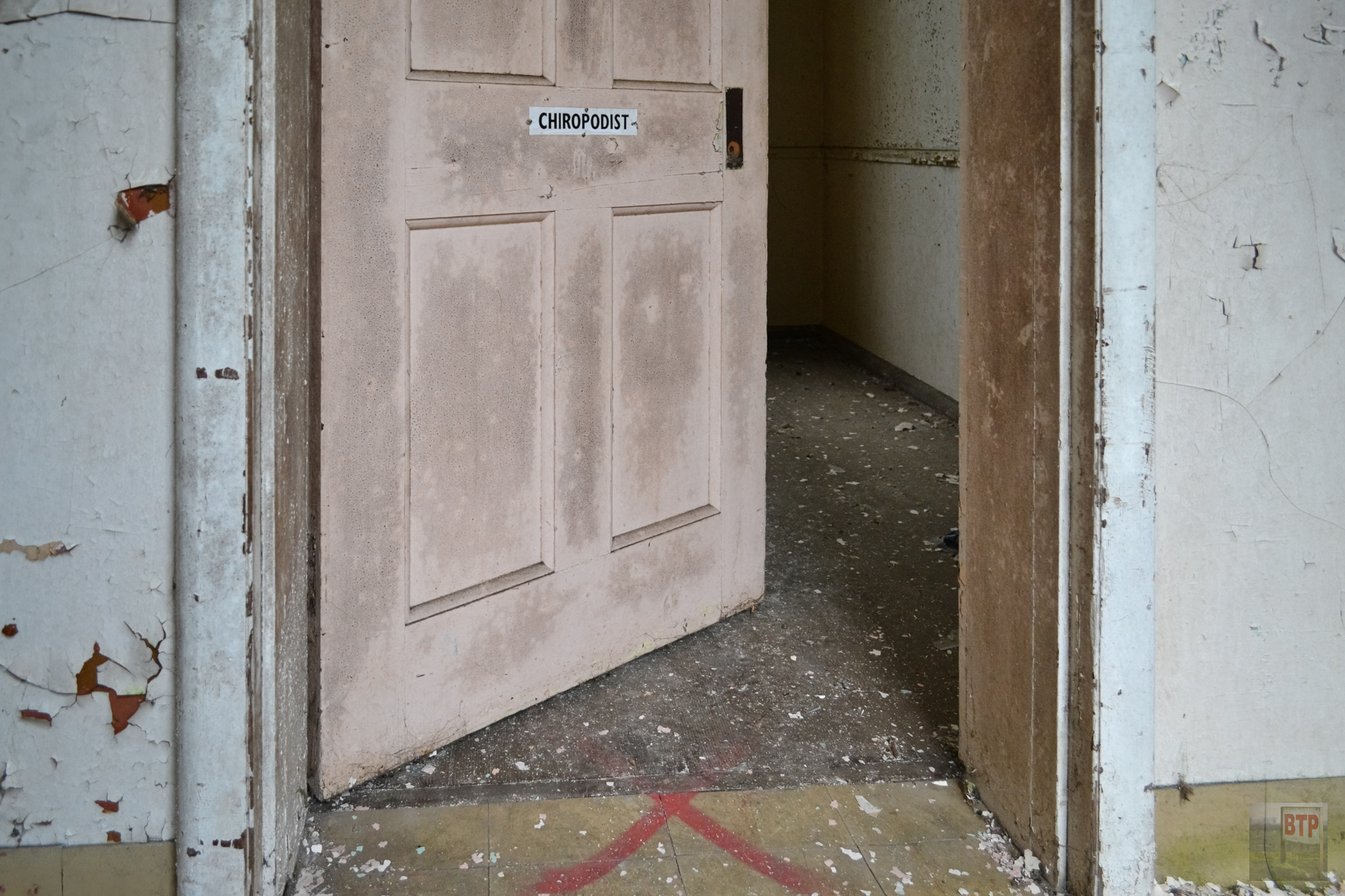

Wards – Siderooms & Seclusion Cells

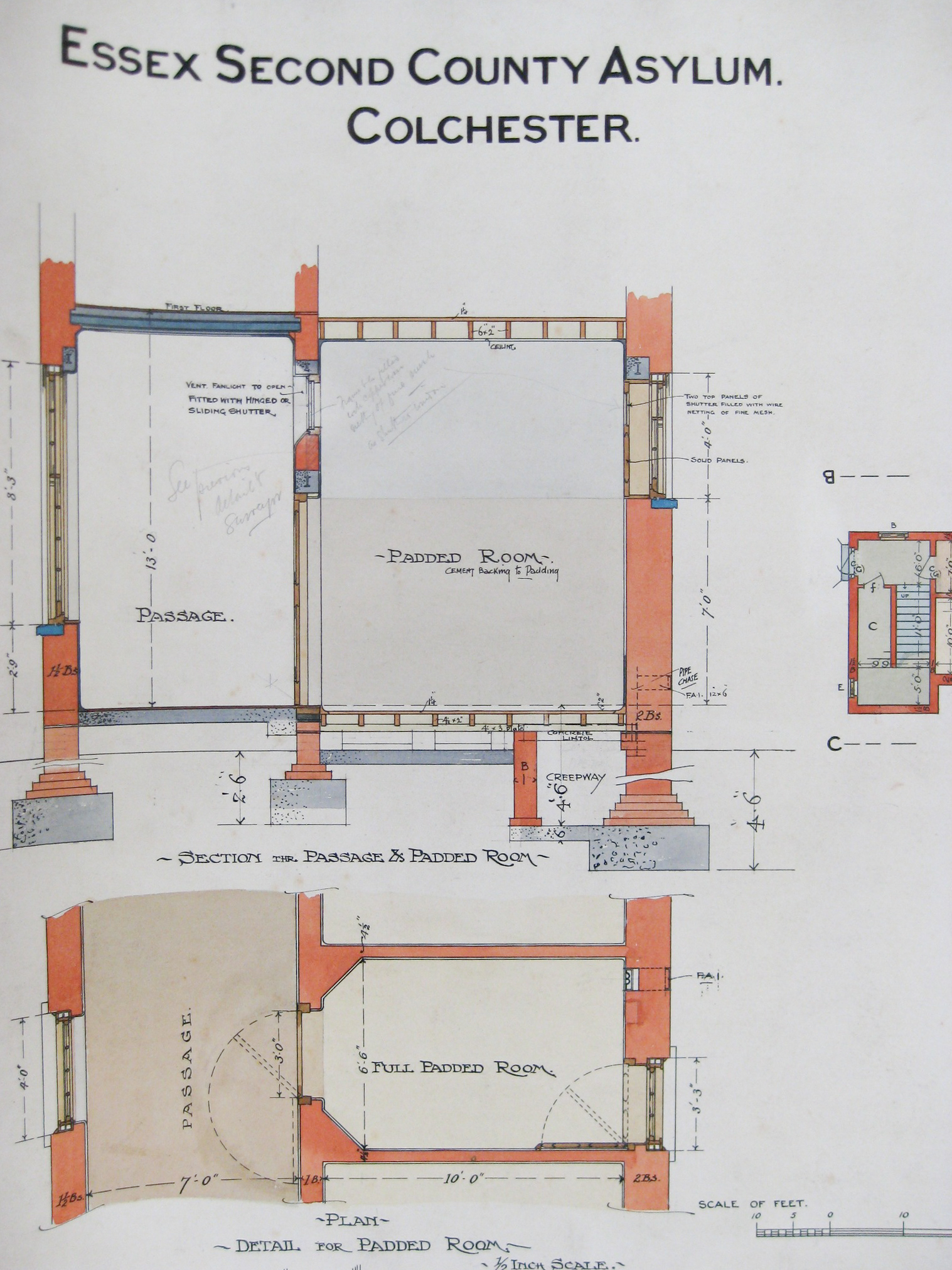

Behind the asylum dayrooms and dorms were the siderooms. These were rows of small singular rooms in a typical asylum fashion, resembling cells. These isolated the patients from the other patients, maybe as punishment or to control them, but maybe to provide some solace and personal space. They often featured wooden window shutters rather than curtains, to prevent suicides using the curtain rails. Some siderooms would simply have been store rooms and offices. The toilets and bathrooms of the wards also backed onto the main rooms.

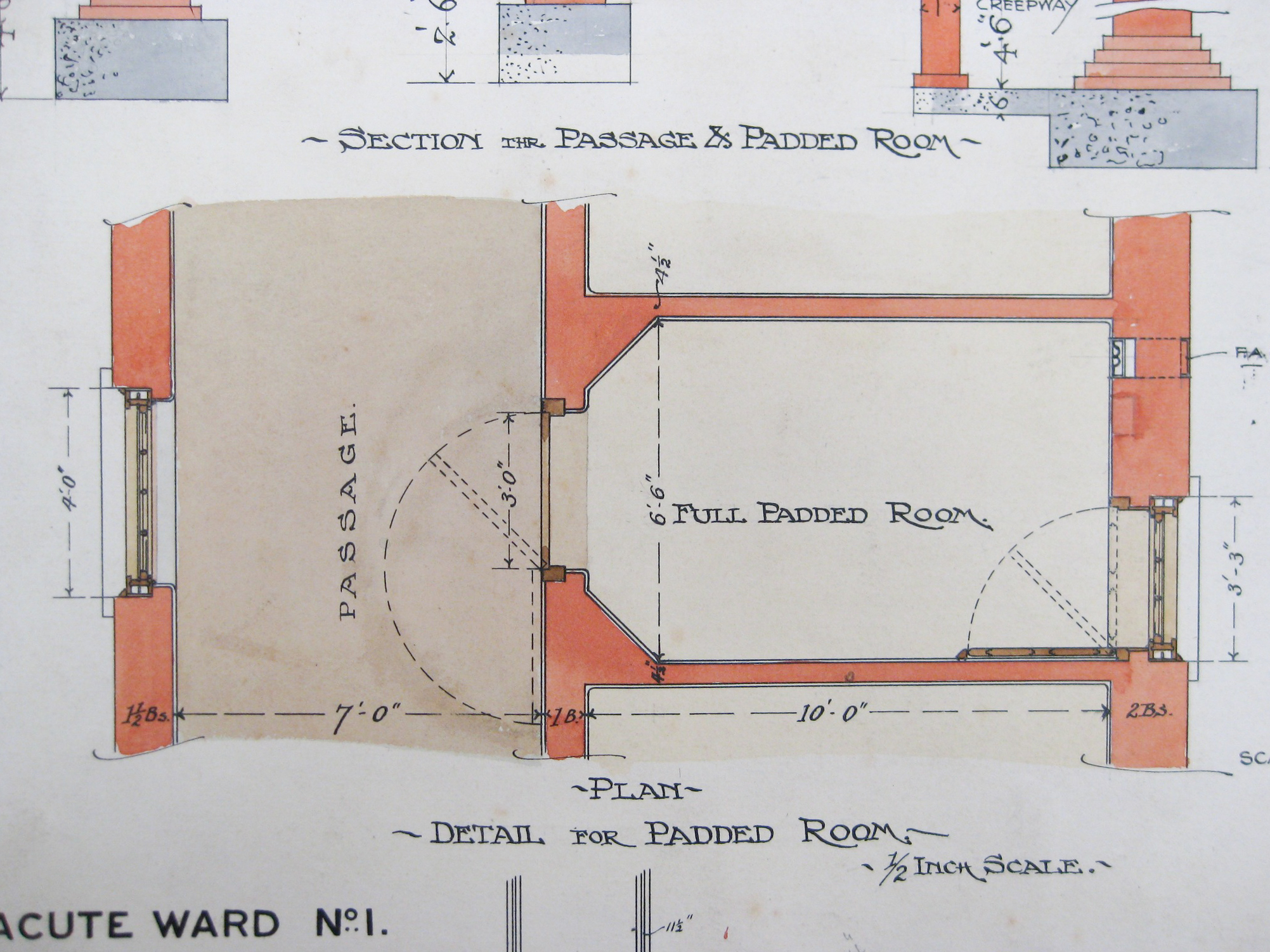

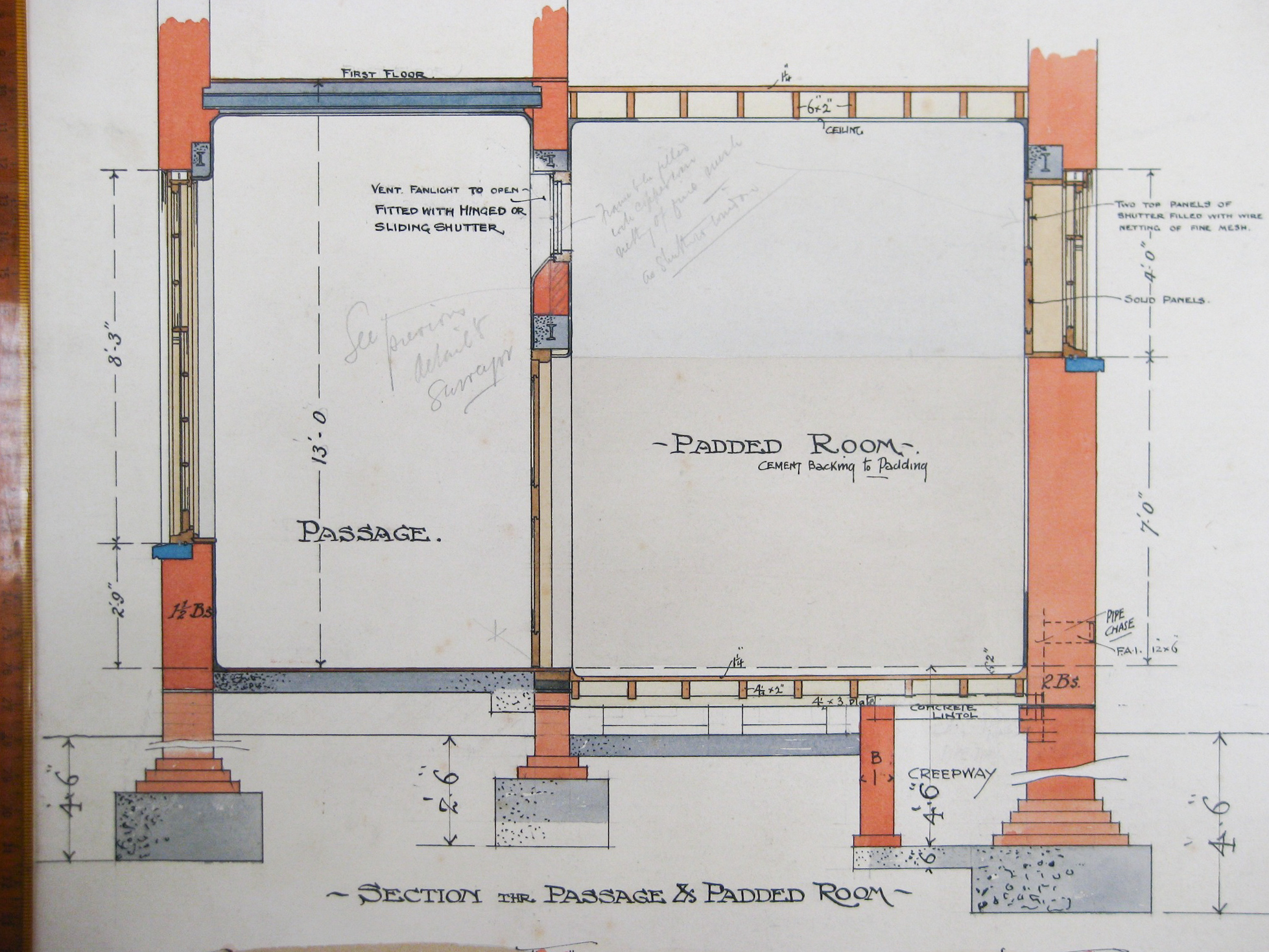

Severalls would have had numerous padded cells originally, although none were known to survive into the 21st century. Some of the padded cells in the villas took the form of larger observation-style rooms. Whether we saw any cells that were once padded, it is difficult to say given that they were at some point stripped out, although there’s nothing obvious in photographs.

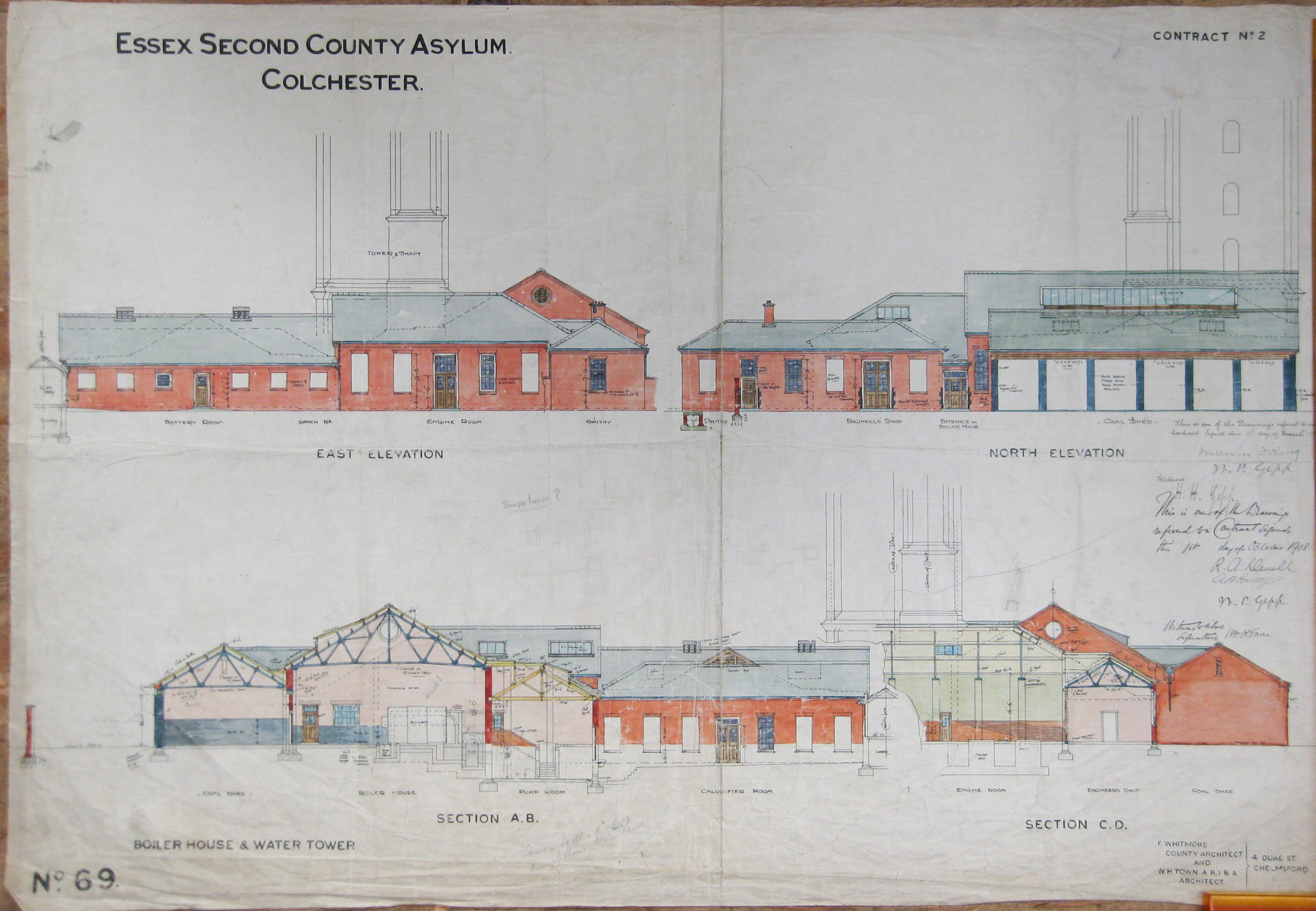

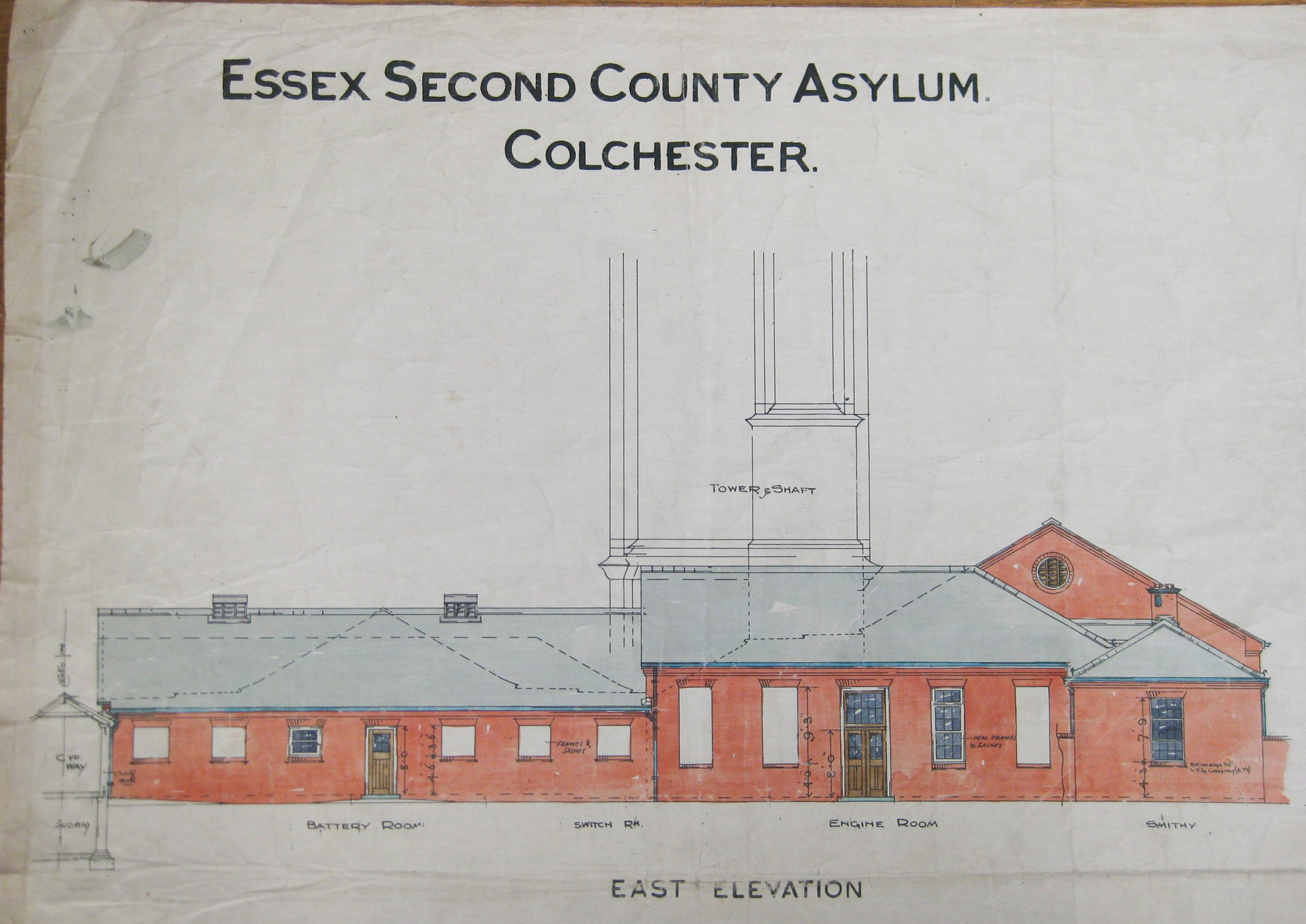

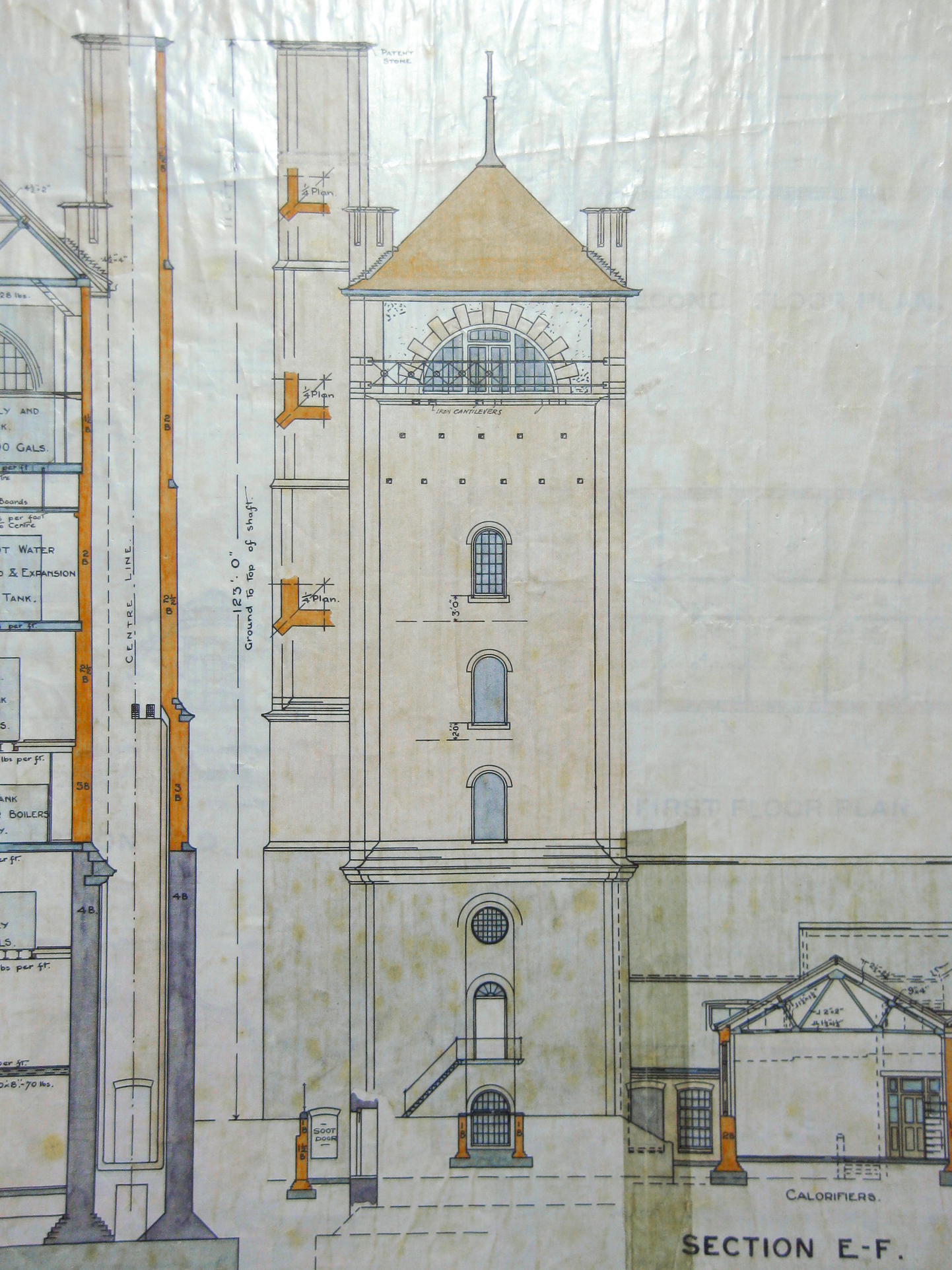

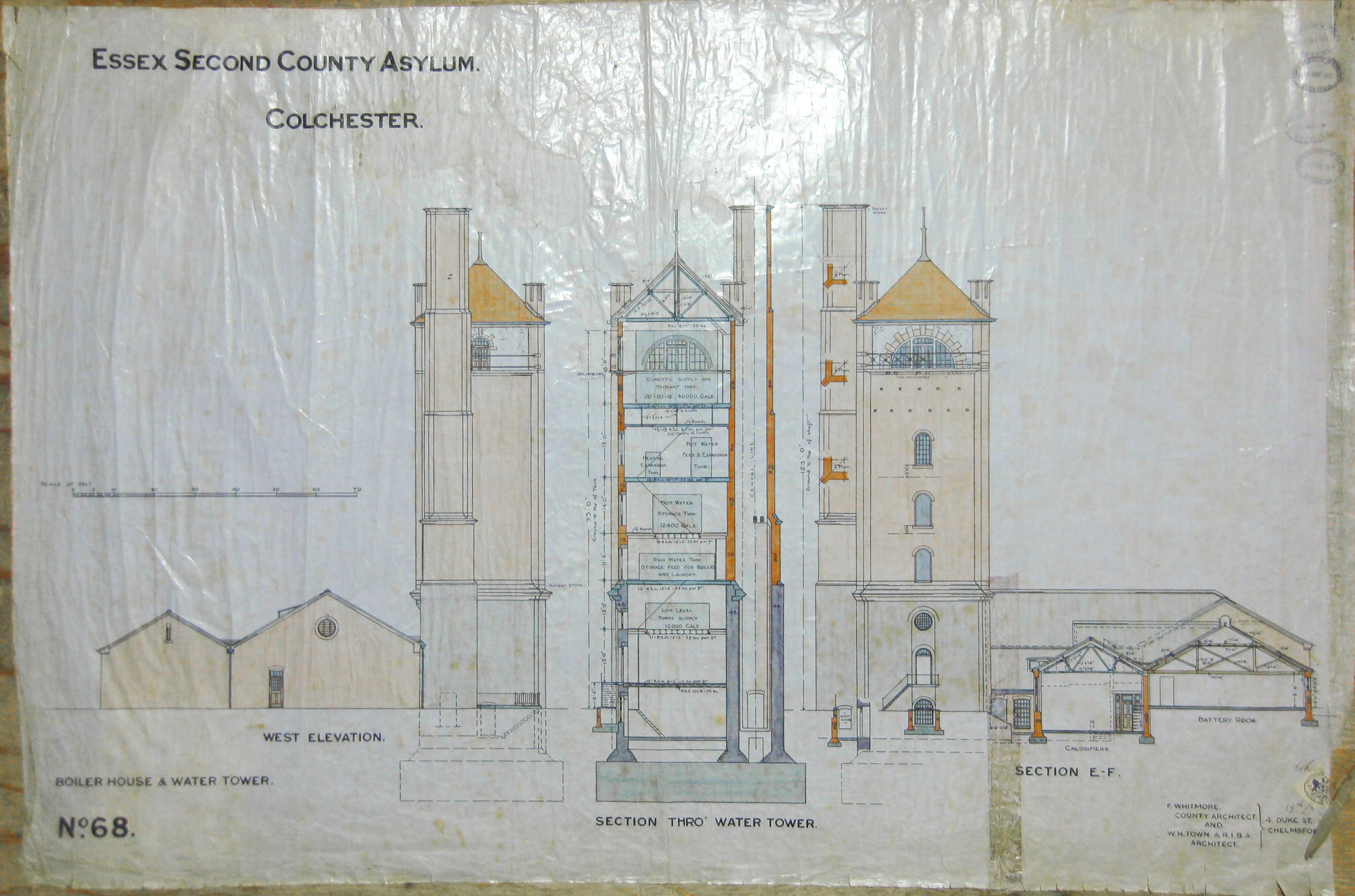

Water Tower & Boilerhouse

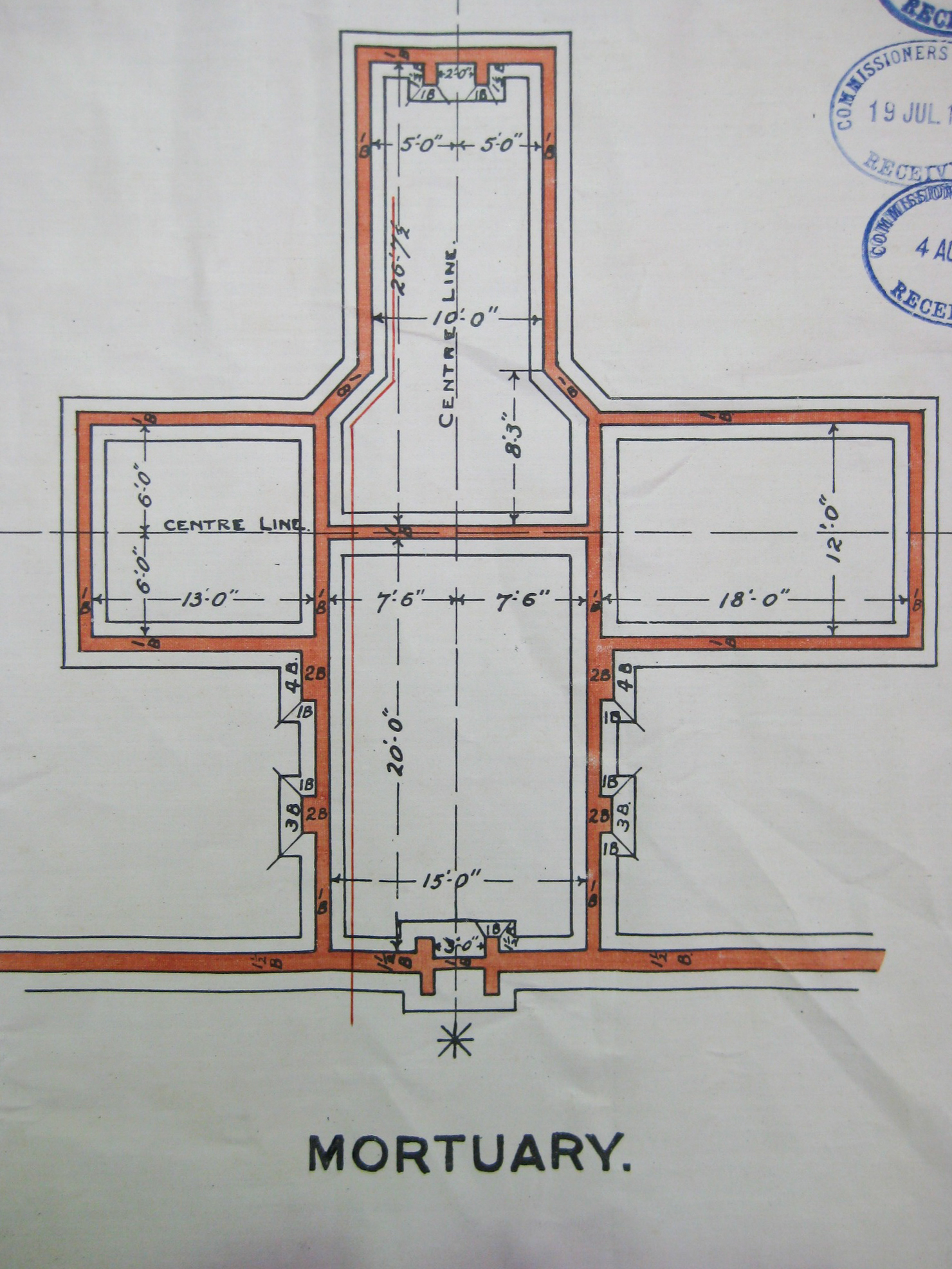

Mortuary

Nurses’ Block & Beta Building

The nurses’ home comprised two interconnected buildings with balconies and walkways. Next to these was the Beta building built c.1930-1935, which served as an overflow of the original nurses’ home. An Alpha and Gamma building were also built for night nurses. These blocks were part of the 1930s’ construction works at the hospital which added additional villas.

Larch House

Part of the original phase of construction, originally the attendants’ recreation rooms hence its proud design, and later serving as an alcoholism unit.

Surrounding Villas

We were shown inside Eden Villa in the south-east of the site, opposite the main building. This was built as the Female Observation Villa during the 1930-1935 phase of construction adding more villas to the hospital.

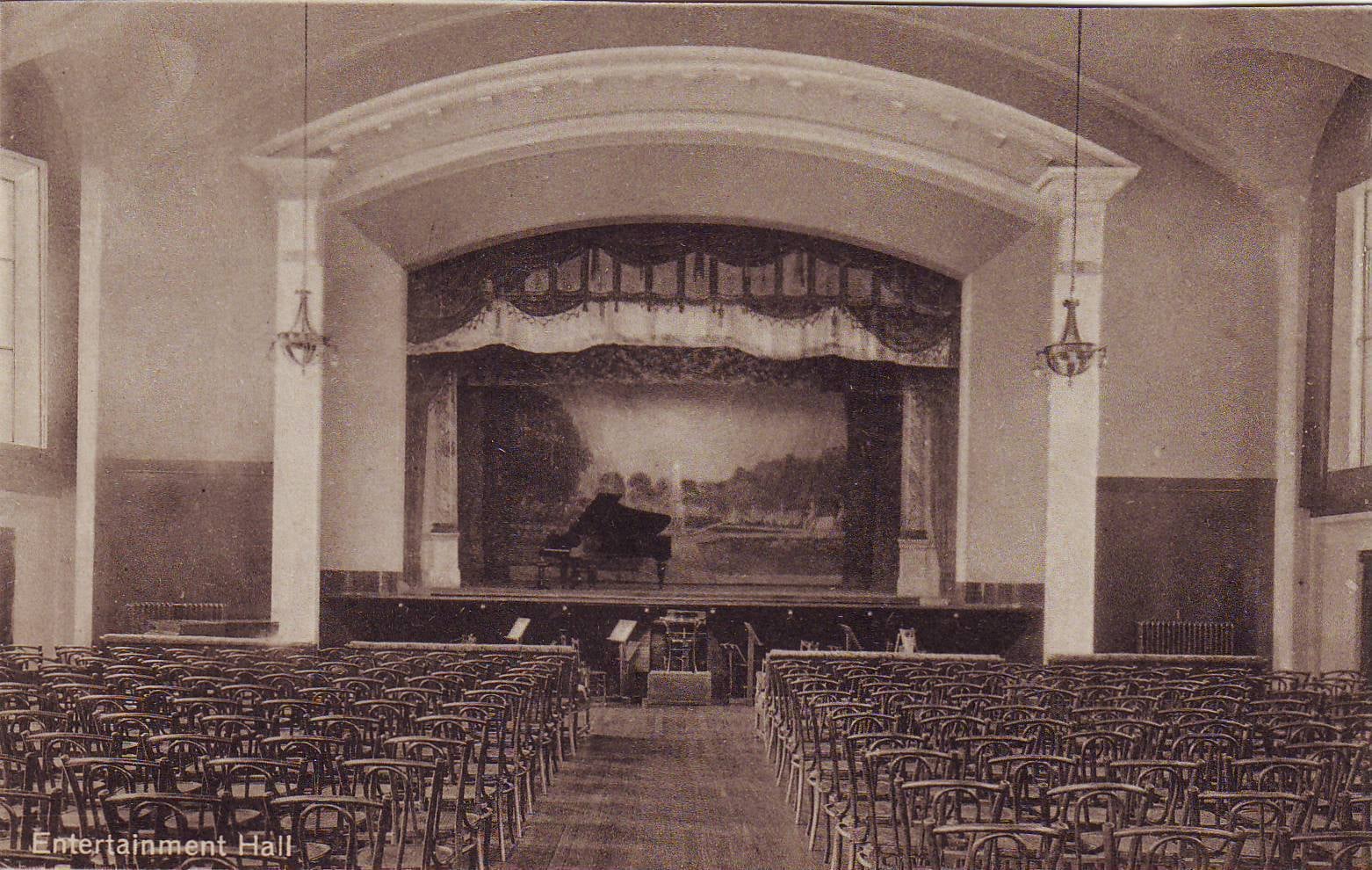

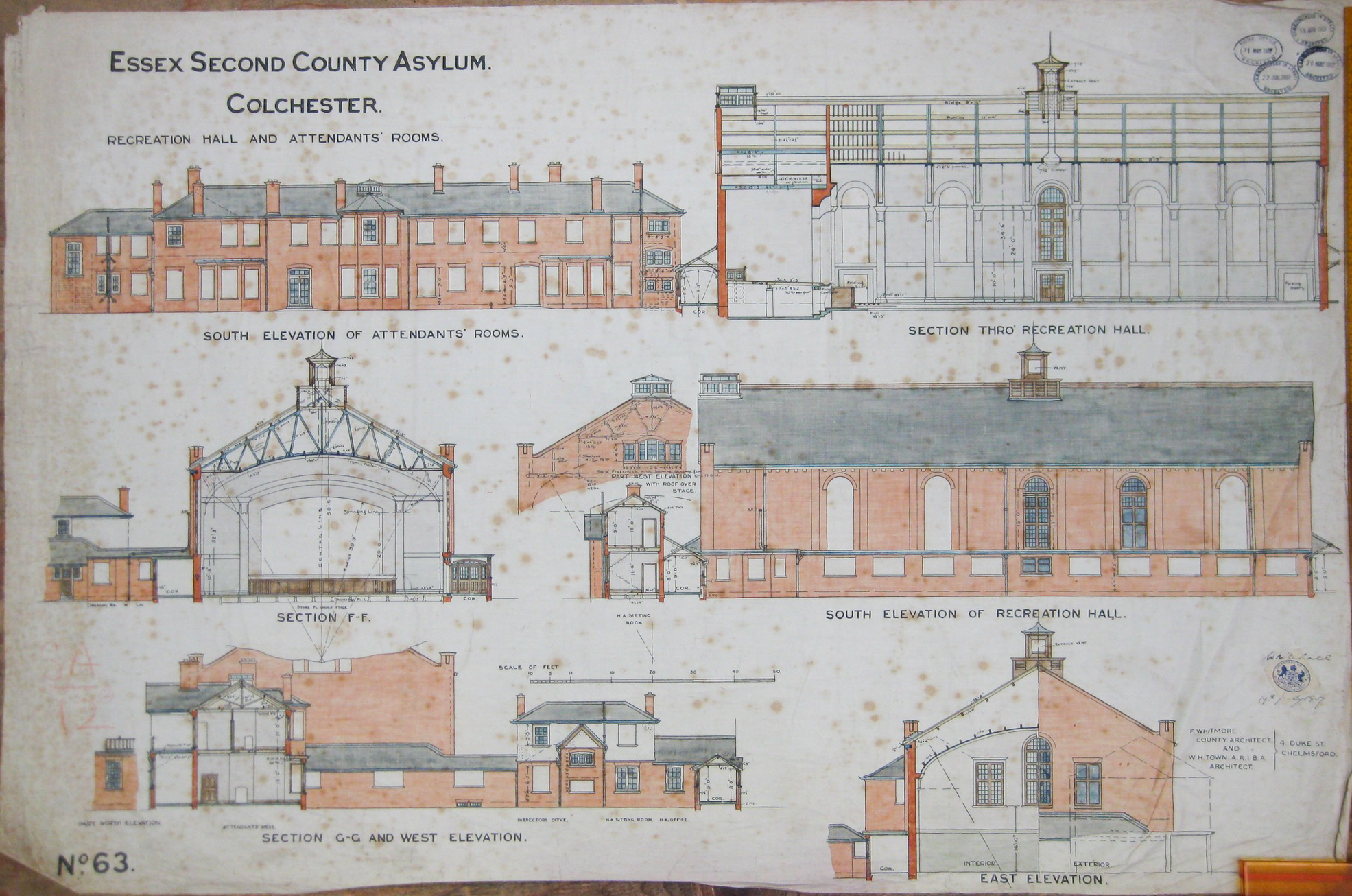

Recreation Hall

Upscaled photographs courtesy of mechanised.org.uk and Trinidunc Stewart of the hall pre- and post-fire, which occurred around 2005. It was subsequently demolished around 2007.

Historic Photographs

Various old photographs of the hospital, largely found at Severalls Hospital Community:

Colour photos by Joe Allen, taken in 1997 pre-closure.

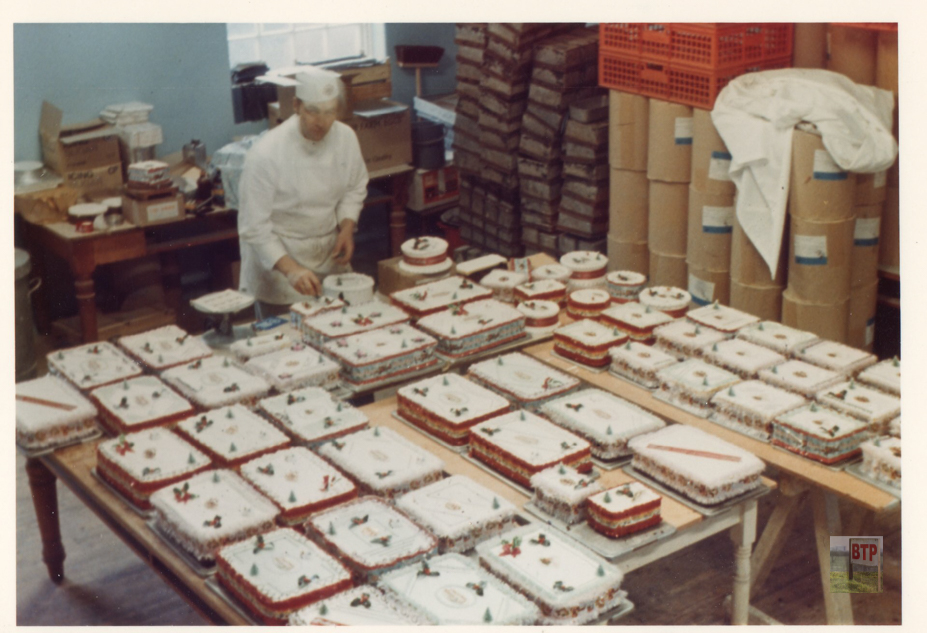

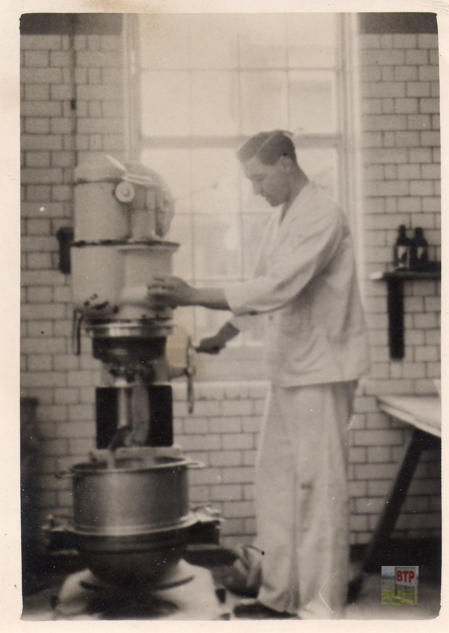

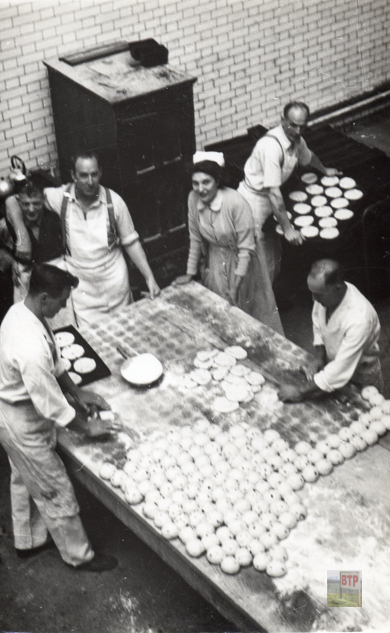

Photographs by Arthur Powell from the Severalls bakery.

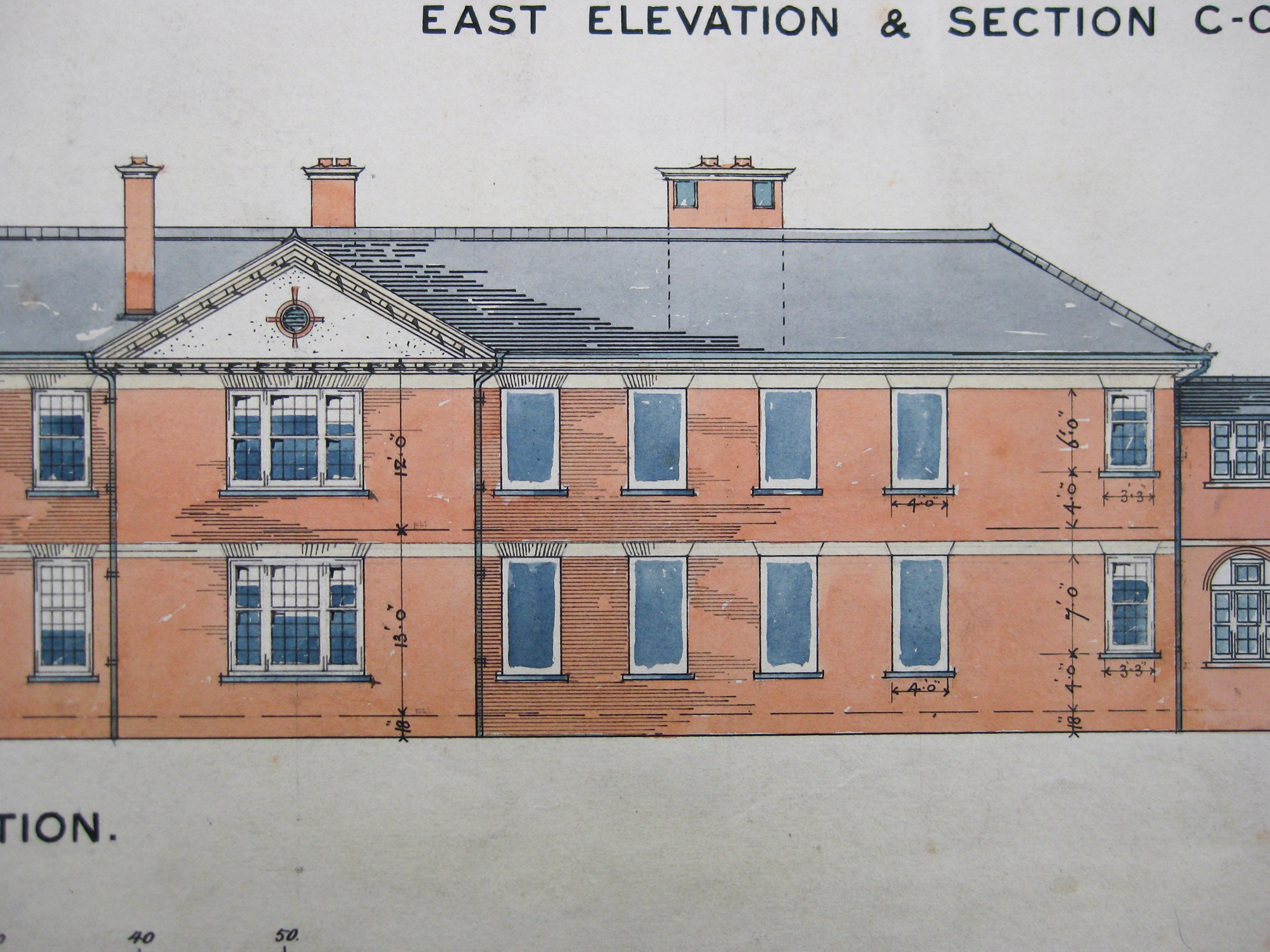

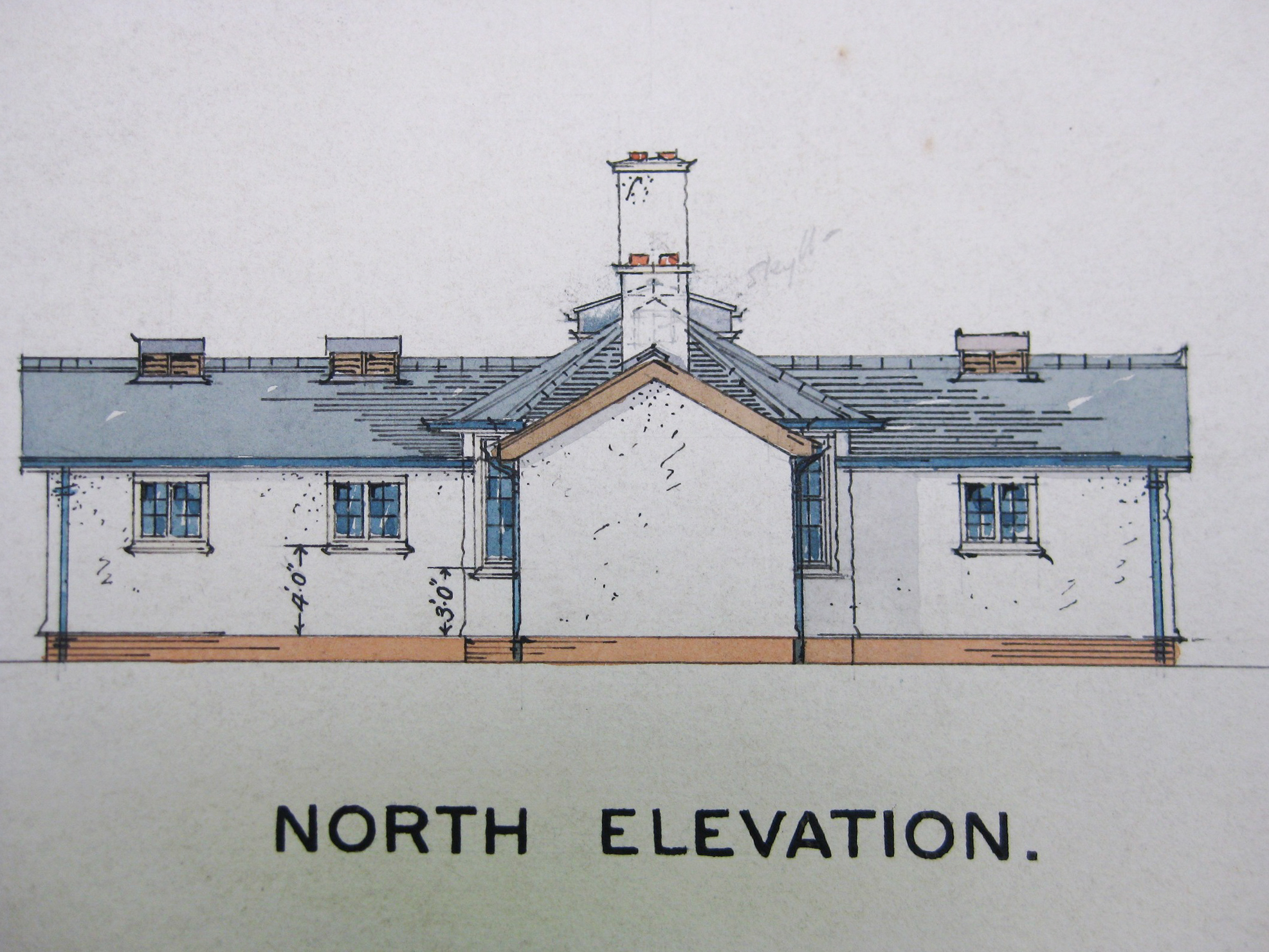

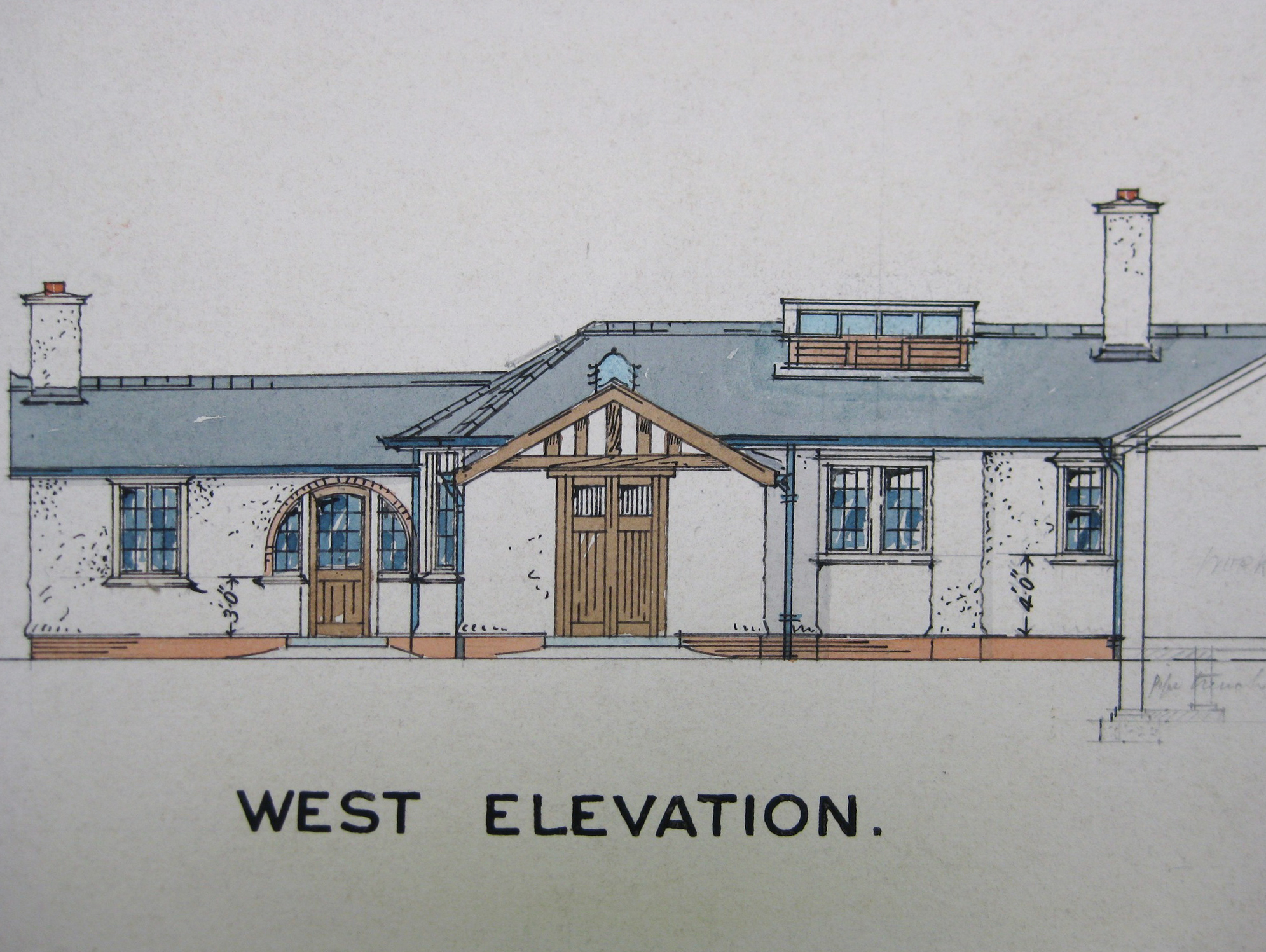

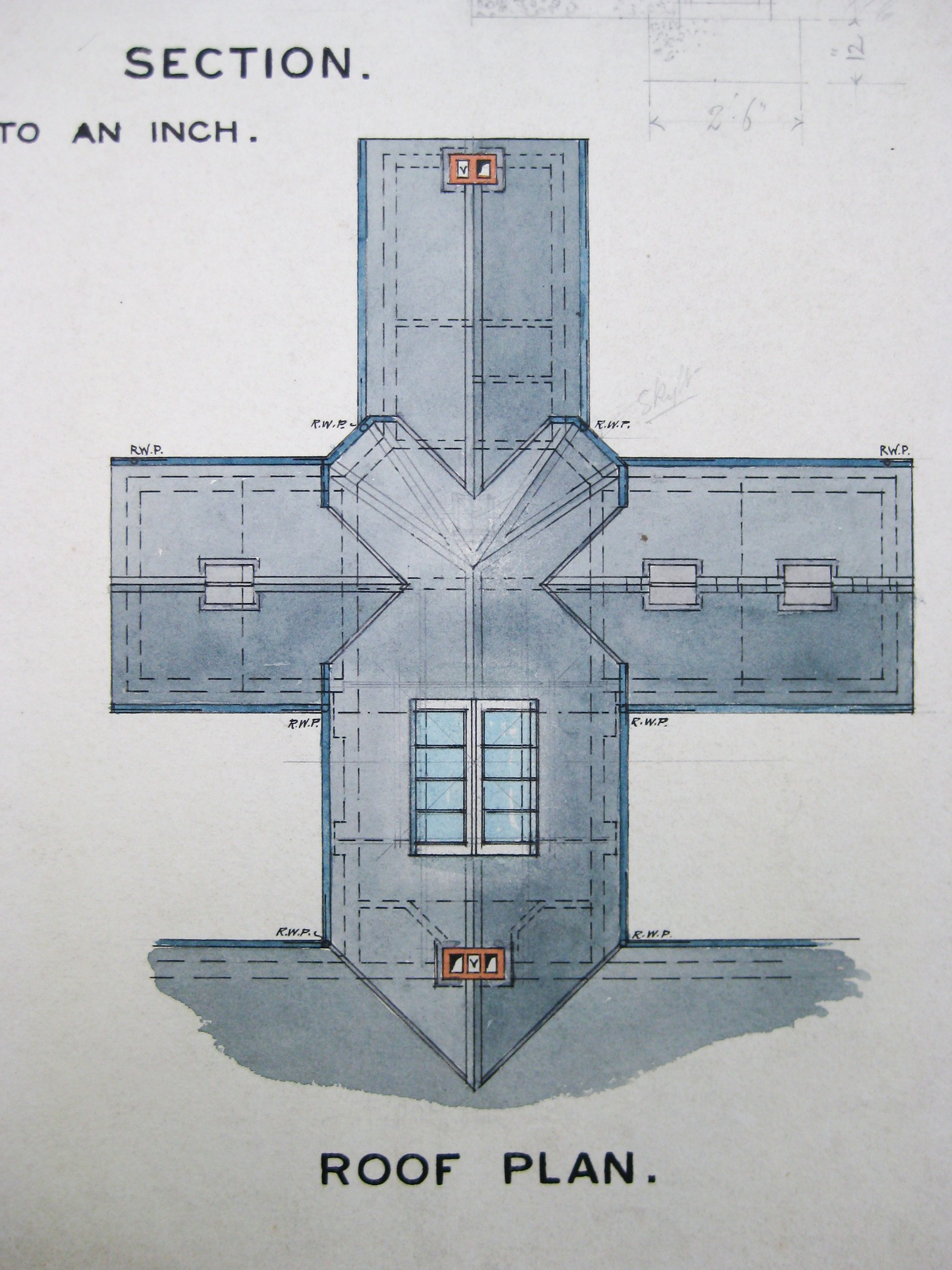

Architects Drawings

These were acquired from the NHS by Trinidunc Stewart, with thanks for allowing us to use them. We have edited the photographs of the plans to correct their perspective and colours to show them in all their glory.

With fantastic support from former staff and patients at the hospital, we set up a dedicated Severalls Hospital Memories group on Facebook. We would also recommend this Severalls Hospital archival page which features a wealth of photographs and documentation of the hospital.

With thanks to the NHS, CountyAsylums.co.uk and Airbourne Imagery for the drone photos.

This entry was posted in Location Report

Pingback: Essex County Hospital - Beyond the Point

Thank you ! I have just discovered your excellent website, and I have a particular interest in the old County Lunatic Asylums in Essex, having worked in a few :

Warley Hospital in Brentwood; Runwell Hospital in Wickford; Severalls Colchester (where two distant relatives died) and Claybury Hospital in Woodford Bridge, now the very exclusive Repton Park.

The treatment regimes in these hospitals were not all bad – a couple of the units at Claybury, for example, were run on ‘group therapy’ lines.

Overall, the closure of these institutions has resulted in a huge loss of in-patient psychiatric beds. Sometimes, people suffering mental illness really do need ‘asylum’.

sorry, rant over

keep up the good work !

Hi Frances,

Oh that is very interesting, you worked at all of the Essex ‘asylums’ then. Was there much obvious difference between their conditions and practises when you were working at them? If you have any material left over, we’d love to see it.

It’s a good point that you make, we would in fact agree. This article isn’t necessarily saying the asylums were all bad, far from it, although there is no doubt that some of their practises and approaches were less than adequate. It’s a very contentious debate but the overall narrative that seems to dominate historiography is that the asylums started with good intentions and a holistic approach to mental health, but suffered after the war when the government did a U-turn on them and their institutionalised shortcomings only spiralled. However, I’m sure there were also improvements in understanding and approaches to care that did either remain at a good standard or develop for the better. It goes without saying that there is clearly a lack of welfare available for those on the streets today that would benefit from institutional care and perhaps are unable to look after themselves.

Thanks for the contrubution,

Liam

Does anyone have a comprehensive list of Severalls Hospital ward names + function for the 1970s? I realise that some wards changed their functions. I have no idea if such records exist – hard copy or online – but I have yet to find such a thing. If we are not careful, this information might get lost.