During the early Second World War, Germany bombed British towns, cities, and industries using aircraft. This initially took place in daylight leading up to the Battle of Britain, but when this tactic failed, Hitler decided nighttime bombing would give an advantage. In the Blitz of 1940 and 1941, the daytime was ordinary, but every night the country’s population would have to confront the possibility that they may not see the following day. Anti-aircraft batteries were built across the country to fire at enemy aircraft. As the Blitz emerged, these batteries were fitted with searchlights to track enemy targets at night. Whilst a multitude of temporary light AA batteries existed, heavy anti-aircraft batteries were more permanent constructions and are what we can usually find surviving today. North of Dagenham, in Chadwell Heath on the outskirts of East London, exists an HAA battery still displaying numerous structures that often do not survive in other examples. Not only this, but it housed eight rather than the usual four gun emplacements. Today it lies in a field recently reclaimed from a deep quarry. Its remains are impressive but it has sadly been subjected to vandalism.

Why is this site important?

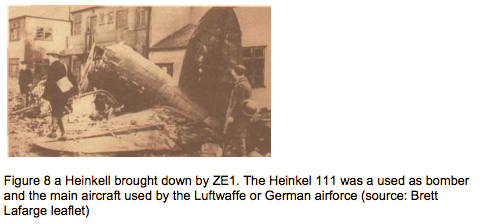

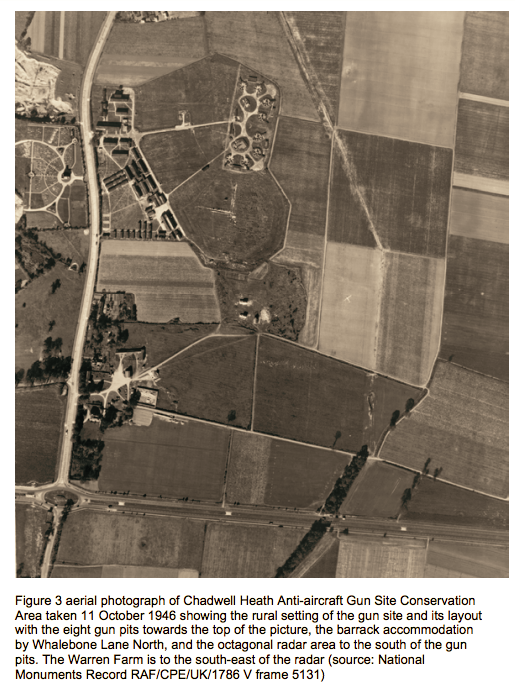

The battery was located on high ground so that it had strong views in all directions so that it could defend London and the surrounding area. Today, you can still get a roughly 360-degree view far around. The battery was built on land containing natural gravel deposits, hence its modern use as a quarry. For some time, the battery stood in a fenced compound in the centre of the quarry site until it was reverted to fields only a couple of years ago. The battery is a Grade II listed structure, and is historically important because it lies in the Inner Artillery Zone defending London. This battery was ‘codenamed’ ZE1 in its day, and is the last surviving battery in the north-east IAZ. Furthermore, this gun battery did actually see action rather than just being a built as a precautionary measure. During the Blitz, ZE1 was allegedly in action for 76 consecutive nights! As well as protecting civilians, the battery would have also protected industry on the Thames at Dagenham; such as the famous Ford factory which at the time was producing armoured vehicles. Towards the late war, air raid via German planes was rare. Instead, ZE1 would have engaged unmanned V1 ‘Doodlebug’ flying bombs.

What structures survive today?

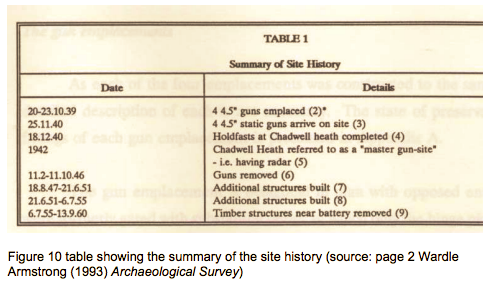

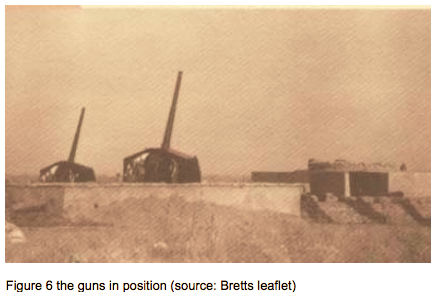

Accommodation huts for those working on the battery was situated off of Whalebone Lane to the immediate west of the battery. To the immediate south was an octagonal radar area used from 1941, and was ploughed up in 1951. The use of radar increased the effectiveness of batteries at night and in their ability to select individual targets rather than fire loose barrages and hope for a hit. Eight gun pits survive and these would have housed 4.5 inch guns. The holdfast bolts which would have held the guns to the ground still survive. The northern set of gun pits have thick concrete ammo stores attached to their exteriors, featuring channels cut into the floor for cabling. These could have been made to adapt to the electrification of gun control as the war progressed. Also on the exteriors of the gun pits were underground corrugated iron air-raid shelters for the crew, which only survive in fragments. The 4.5 inch guns were later changed up for 3.7 inch guns which although often seen as less desirable as 4.5 inch guns on HAA batteries, they were lighter and more flexible at tracking targets. Around the edges of the gun pits are cuboid lockers for ammunition. Some still contain their metal doors and racking timbers with cut-outs for shells. The ZE1 HAA battery consisted of two ‘halves’; two small batteries put together. Each had a command post sunken into the ground, as well as four gun pits and two large blast-walled magazines for ammunition storage. Whilst we unfortunately missed the northern smaller command post, the southern one was complete with numerous walled areas indoor and outdoor, partially sunken, for the spotting, plotting, and directing of gunfire in the centre of the arc that its four associated gun pits formed. It consisted of several structures including some brick indoor rooms bearing original paintwork, partially with a corrugated iron ceiling possibly for reinforcement against bombing. It also had a central square building with steps leading into it. Its tarmac roof covering was most likely added post-WW2. Because AA batteries were high targets from enemies, they had to protect its occupants from bombing or even enemy assault if Germans invaded Britain in 1940. The battery had sunken machine gun posts around its perimeter and we found one sunken into the ground with a seemingly modern steel roof – maybe a replacement. These are surrounded by grassed earthen bunds to give the command crew protection and a low profile. The magazine buildings are large rectangular concrete huts with heavy cast-iron doors. One of these featured some interesting brick tiered shelving and benches inside – probably for ammo storage or preparation. Several structures on site were built in the Cold War incase of Russian aerial attack. These included a double concrete breeze-block garage and numerous other mysterious structures. A probable vehicle store onsite was likely built at this time. Some survive only as concrete bases today. These were built from 1947 to 1955, with a roadway being built as late as 1960. At the entrance to the site, a large and small ancillary hut-type building survive but these are not listed.

What is the future of the battery?

Today, the battery has been sadly subjected to heavy graffiti and vandalism. However, the actual concrete structures and paths survive in a seemingly-stable state with hope of restoration. In the summer of 2008, an unexploded Second World War bomb was uncovered embedded in the ground at the site. It can only be assumed this was intended to blow up the gun battery. It has been designated a Conservation Area by the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham and various associated bodies have been looking into the possibility of restoring the site and opening it up to the public as of 2015. You can see their 2009 PDF survey of the site in the article sources at the bottom of this page. It really would be great to see this gem restored or at least cleaned from graffiti and encroaching foliage. Let’s save it now before it’s too late.

Gun Emplacements

Magazines

Command Post

Various Shots

Wartime Imagery

Sources:

https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/heritage-at-risk/search-register/list-entry/49608

Excellent aerial photograph at top is property of Historic England, as are the ‘Figure’ images in the Contemporary Photographs gallery (taken from PDF report)

Thanks to William Smith aka SuperPopBro for the great artist’s impression of the gun battery old and new at the to of this article

Hi. Informative video. Could you tell me roughly where this is on Chadwell Heath ?