Please note: Some of the terms used in this report are used in a historical context and reflect people’s attitudes and language at the time and may now be considered derogatory or offensive.

As part of our coverage of Severalls Hospital, a former asylum in Colchester, we’re taking a look back at the history of psychiatric institutes and how these grand buildings housed hundreds if not thousands of patients across England and beyond – yet there’s just a handful still in use today.

The level of specialist psychiatric care in the 18th and 19th century was very limited due to little being known about it; it was seen as a physical problem rather than a psychological one. At the start of the 19th century there was an estimated few thousand “lunatics” in various asylums across England which rapidly grew to over 100,000 at the start of the 20th century, starting the rise in asylums being built. In today’s society, asylums aren’t used; the buildings stand derelict, converted into flats or were bulldozed for new houses, leaving behind only memories and untold stories.

Bethlem Royal Hospital, or Bedlam, is one of the most infamous and oldest asylums ever built. Situated in South London, the hospital was founded in 1247 and still remains as a general hospital today. It was the first ever place to specialise in psychiatric care in Europe and has been the settings for many books, films and television series. Built during the reign of Henry III, Bethlem was not initially intended as a hospital, but as a centre for the collection of alms to support the Crusader Church and to link England to the Holy Land. Due to the long term neglect by society, social problems or madness wern’t properly concentrated on until the nineteenth-century, when the attention soon escalated. References to mental health institutions are limited for the seventeenth-century although by the following century the so-called ‘trade in lunacy’ was well established. One of the reasons for Bethlem being infamous is because they allowed the public to pay to watch ill patients for entertainment. This “display of madness” may have been decided as early as 1598 as means of raising hospital income.

In the late 17th century, this model began to change and privately run asylums for the insane began to rapidly increase and expand in size. Already in 1632 it was recorded that Bethlem Royal Hospital, had “below stairs a parlor, a kitchen, two larders, a long entry throughout the house, and 21 rooms wherein the poor distracted people lie, and above the stairs eight rooms more for servants and the poor to lie in.” The vast majority were small in scale by 1800 with only seven asylums outside of London with in excess of thirty patients and somewhere between ten and twenty institutions had fewer patients than this.

During the 1800’s attitudes towards the mentally ill began to change. It was viewed as a disorder that required compassionate treatment that would help the person to get better. King George III, suffered from a mental disorder which lead to a change in attitude that mental illness was seen as something which could be treated and cured. The introduction of less physical treatment was introduced by French doctor Philippe Pinel, who specialised in researching humane treatment to the custody and care of psychiatric patients.

English businessmen William Tuke led the development of a radical new type of institution in northern England. In 1796, with the help of fellow Quakers, he founded the York Retreat, where around 30 patients lived as part of a small community in a quiet country house, engaging in a combination of resting, talking, and light manual work. Rejecting any medical theories or techniques at the time, this centered around minimising restraints. This inspired similar institutions in the US and later led to an extensive overhaul of mental health care in the UK.

In the early 19th century mental health reforms were being introduced with a large state-led effort. Public mental asylums were established after the passing of the 1808 County Asylums Act which gave magistrates the power to build partially state funded asylums in every county across England. Nine counties first applied, and the first public asylum to open was in Nottinghamshire in 1812. As part of the reforms, Parliamentary Committees were established to investigate and iron out abuse at private madhouses such as Bethlem Hospital. National attention was turned towards the routine use of bars, chains and handcuffs and the filthy conditions that patients lived in. However, it wasn’t until 1828 that the newly appointed Commissioners in Lunacy were empowered to license and supervise private asylums. The introduction of the act was an important landmark in the history of psychiatric care, as it changed the status of mentally ill people to patients who required treatment.

The Act created the Lunacy Commission, which as part of the reforms, was made up of eleven Commissioners who were required to carry out the compulsory construction of asylums in every county, with regular inspections on behalf of the Home Secretary. All asylums must of had a resident qualified physician but although reforms were still taking place, the admission of people to asylums was still of concern. Women could be sent there if men thought that they had strong opinions or if they were struggling to cope in a family. A doctor would be called to assess a potential patient after someone was labelled ‘insane’ on social terms, or had become socially or economically problematic with not much difference between a lunatic and criminal lunatic. The fear was that people were becoming a source of embarrassment to their families would cause them to be sent to asylums causing a surge in cases. At the turn of the century, England and France combined had only a few hundred individuals in asylums, but by the end of the century this number had risen to the hundreds of thousands. The United States housed 150,000 patients in mental hospitals by 1904 while Germany housed more than 400 public and private sector asylums.

Despite this, the hope that mental illness could be seen in a new light through new treatment options during the mid-nineteenth century, was disappointed. Psychiatrists were becoming under increased pressured by an growing patient population. In the United States alone, the average number of patients in asylums jumped by over 900% with numbers in England not far off. With asylums becoming overcrowded and psychiatrists overworked, they were turning back to prison-like conditions with the reputation of psychiatry in the medical world hitting an extreme low.

Treatment Advances

A series of radical physical therapies started to be developed at the start of the 20th century, with this perhaps one of the strongest reasons for asylums having a bad reputation. Austrian psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg’s came up with the treatment of a malaria injection for general paresis of the insane (GPI) which proved successful in treating dementia praecox, known today as schizophrenia, which was thought to be a hereditary and untreatable disorder, this was first used in 1917 and went on to win him a Nobel Prize. Following the discovery of this, more experimental and now thought of as controversial, experiments were carried out, not just in Europe but across the globe. In 1933 the Vienna-based psychiatrist Manfred Sakel introduced insulin shock therapy and in August of the following year, a Hungarian psychiatrist introduced cardiazol shock therapy, which was the first seizure therapy for a psychiatric disorder.

Both of these therapies were initially targeted at curing dementia praecox. Cardiazol shock therapy, was superseded by electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), after this was invented by an Italian neurologist in 1938.

The use surgery to cure a mental disorder was introduced in the 30’s. Egas Moniz performed the first lobotomy in Portugal in 1935, a procedure which targets the brain’s frontal lobes. From 1946, Walter Freeman developed the transorbital lobotomy, an “office” procedure which involved using a device like “an ice-pick” which did not have to be performed in a surgical theatre and took as little as fifteen minutes to complete.

Freeman is credited with the popular rise of this treatment in the US and by 1951, over 18,000 people had undergone the controversial procedure even including the sister of President John F. Kennedy. A 2009 medial publication reveals that under Nazi control in 1939, around 6,000 disabled babies, children and teenagers were murdered by starvation or lethal injection as part of a euthanasia campaign.

The Rise in Asylums

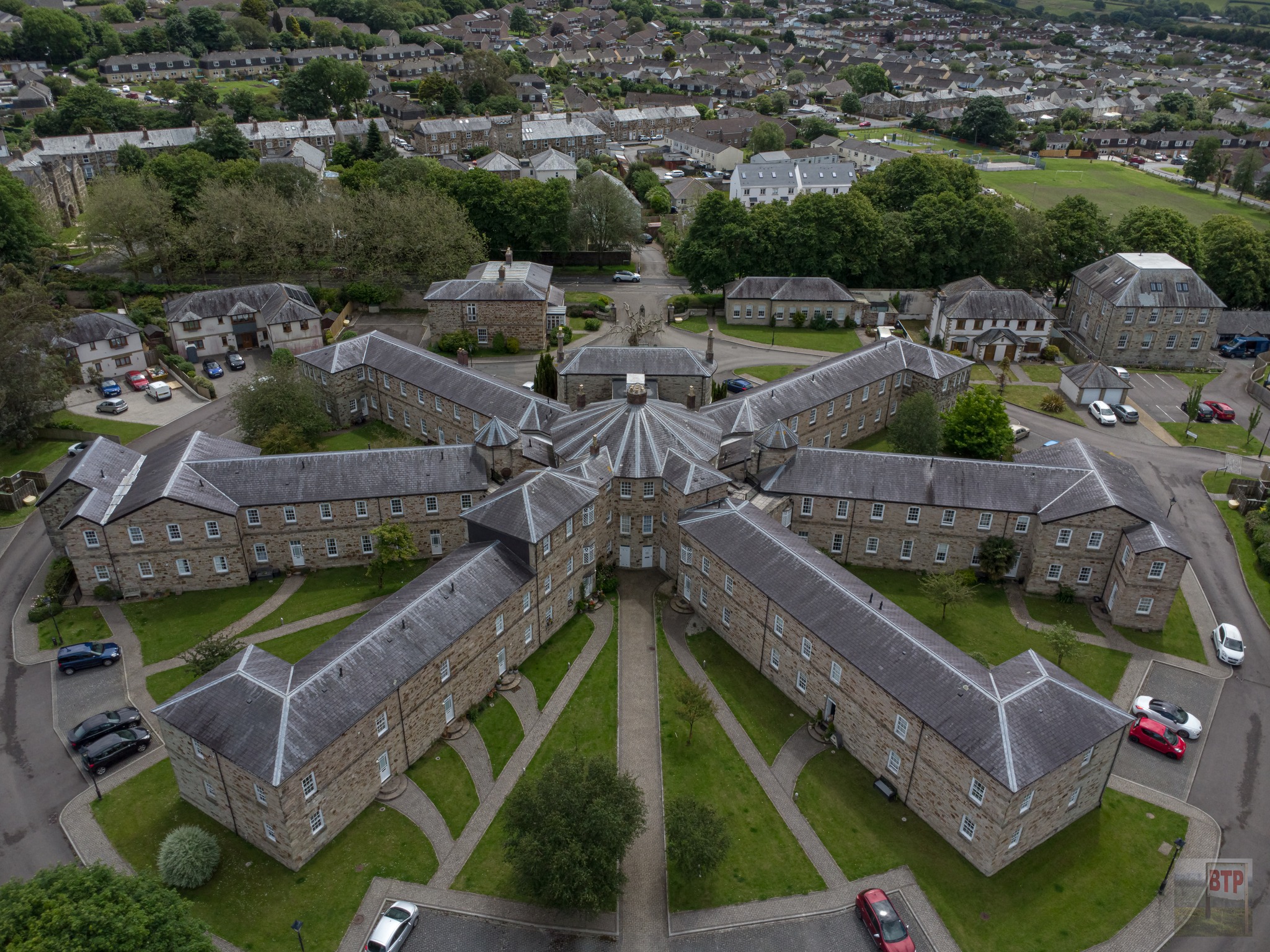

Asylums were now being built at a rapid rate. They were specifically built in secluded areas just outside of towns as an effort to keep the mentally ill away. Surprisingly, the buildings were grand in scale and design, spanning many acres. Walking through the miles of corridors, you would commonly find a grand administration building, dance hall, laundry and bakery facilities, powerhouse, villas, a water tower and many more areas to keep the asylums a self contained community with patients or staff never having to leave the site. Farms were also used at many asylums to provide light work duties to patients and also to provide them with food.

There are many architectural and design styles of asylums with many were based around the Echelon plan where all wards and offices were connected by corridors meaning that staff would never have to go outside. This revolutionised asylum design due to the practicality and light and airy feel to the hospitals – something very important for mental health. This article on TheTimeChamber details the various layouts. London architects Elcock and Sutcliffe designed many asylums including Runwell. They were at the forefront of industrial design at the time, having designed many other asylums including the infamous Bethlem Royal Hospital. They travelled to many asylums across Europe and the United States to get inspiration for modern hospital designs and layouts.

Inside the Padded Cells

Restraints were used in the early days of asylums as a way of restraining patients to prevent them from hurting themselves or others. Lincoln Asylum is regarded to be the first which abolished restraints after a patient died there in 1829 when he was strapped to his bed and not checked throughout the night. Staff at Hanwell Asylum, which opened in 1831, adopted similar policies where patients would be isolated rather than restrained.

Unruly or aggressive patients patients would be isolated in a room on their own to calm down, and monitored by staff who would intervene if they started to harm themselves. These small rooms, with minimal or no furniture, would often only have a small window and the walls and doors padded to stop the patient hitting their head against anything hard. Some asylums, like St Cadoc’s in Newport, even had radiators on the ceiling.

It wouldn’t be uncommon for patients to die at asylums, especially as a lot of patients were elderly. Most asylums had mortuaries which were usually located next to the maintenance department with easy access for vehicles. It’s possible that the patients and staff may have been buried in the grounds of the on-site chapel. Whilst photographing Warley Asylum we found the grave of Sarah Jones, a 58 year-old who worked at the hospital for 25 years as a laundress.

Water Towers and the Demise of Asylums

There they stand, isolated, majestic, imperious, brooded over by the gigantic water-tower and chimney combined, rising unmistakable and daunting out of the countryside – the asylums which our forefathers built with such immense solidity to express the notions of their day. Do not for a moment underestimate their powers of resistance to our assault. Let me describe some of the defences which we have to storm.

These were some of the words spoken in Enoch Powell’s famous Water Tower Speech in 1961. The Minister of Health boldly wanted change in the way that psychiatric health care was delivered, believing that these mental hospitals were outdated relics of the past. His pledge to tear them down didn’t have much luck, by the mid 1970’s, Powell would have hoped that all, or most, of these institutions would have closed – but not a single one had, with around 100 standing across England. He wanted general hospitals to have specialist mental health units or preferably for patients to get care in the community. This deinstitutionalisation phase is arguably as big as the rise of the aslyums.

Throughout the 1980’s and 90’s the hospitals were closing on by one, much to the delight of Enoch Powell, but not perhaps to everyone else. Some patients had been living in these mental hospitals for years, some for even 20 or 30 years and were use to environment and care that they provided. Moving into an open society would be a big change for them, with no 24/7 support and care. It also changed the perception of the mentally ill, as they were no longer being locked away behind closed doors.

In December 1992, headlines were made when a schizophrenic stabbed a newly-wed musician in the eye at Finsbury Park Tube Station, killing him. Christopher Clunis was jailed but the public were shocked to learn that Clunis has had a history of violent behaviour and had recently been released under the Care in the Community scheme, prompting fear again for the mentally ill. A BBC documentary in 1997 features psychiatrists and police working together to raid the homes of mentally ill patients – a very different side of care in the community. Releasing thousands of ill people from asylums raised a new set of problems and with tougher action from the Government and the police, many people felt like this was a step backwards.

Derelict Places

Runwell Hospital closed in 2010 and was one of the last from the asylum era to close. High Royds closed in 2003 and Severalls in 1997. Many of the buildings were either left derelict, or the sites were sold to developers. Many of the derelict sites were left to the elements and many Urban Explorers have taken to exploring these derelict sites.

Asylums We’ve Documented

Barrow

Cane Hill

Cefn Coed

Gartloch

Glanrhyd

Glenside

Hartwood

High Royds

Mapperley

Mid Wales

Murray Royal

North Wales

Rauceby

The Retreat

Ridge Lea

Rosslynlee

St Andrew’s

St Cadoc’s

St David’s

St John’s

West Riding

Whalley

No mention of Broadgates in Walkington near Beverley I went round it in 1992 as it was being demolished I have some photos if u want me to scan them for u…