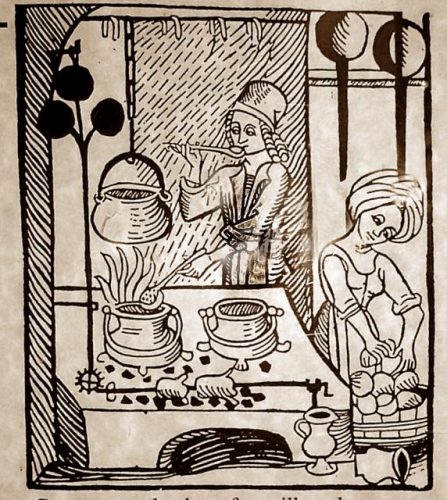

Cooking something up in the kitchen is always good fun, but even more fun when you try and produce a type of food completely alien to modern day cuisine. This is what I did aided by cousin Merlin one cold day when I fancied exploring history a bit differently this time. It was a great way to get behind the way people actually thought about food over seven centuries ago. What I began to realise was that people didn’t just eat different things, but they combined ingredients people wouldn’t dare attempt in any professional restaurant today; yet they still had surprisingly successful results. Who would’ve thought you can make jelly from breadcrumbs?

How exactly did Medieval food vary to what we eat today? In some ways, not much- they still ate soup, stew, roast meat if you had money, and regardless of money lots and lots of bread. Obviously processed food is far more available today – its easier to eat a ready-made meal than it is to grab basic ingredients, causing a backlash of pro-healthy eating interest in raw fruit, veg, and even unprocessed meat. This is arguably the result of technology becoming so advanced that it is effortless to manufacture food, giving people a desire to return to simpler times. However, would you believe that in the Middle Ages people desired to have their food produced as much as possible? Raw stuff was just not popular. Perhaps this was a way to avoid eating nasties and getting sick, or just a result of fashionable refinement that frowned upon having raw foraged plants straight from the outdoors. Either way, foods like pottage were essentially stews slow-cooked to reduce the contents to a homogeneous mass. The thicker and therefore more broken-down the pottage was, the more refined the dish.

Meat was less-commonly eaten by peasants apart from that of pigs, because they could find their own food such as acorns in the woods and could rough out the winter just fine by themselves so were cheap to keep. Believe it or not, sheep were slender, the size of dogs, and had long tails, so were worth more kept for wool than slaughtered for meat. Hunting game in the lord’s domain was punishable by having your hands cut off as a peasant, so wild animals were a no-go, and birds would’ve been difficult to hunt before shotguns and air rifles existed. Therefore brown rye or barley bread and vegetables were the mainstay for peasants, and in the afternoon whilst working in the fields villagers would eat a ‘ploughman’s lunch’ – bread, cheese, and ale. Those living by the sea might be able to take advantage of seafood. Nobility and those with money could enjoy meat, sugar, imported spiced, fish from ponds, and white wheat bread fairly similar to that of today. People would drink mainly weak ale made from barley, as it was safer and more pleasant than water, although milk too was drunk. Of course fermentation would make water safe to consume, so even children would drink ale.

We decided to make three recipes; peas pottage which was a staple working-class main course, cherry pottage which would’ve been a fine dessert for those who could afford sugar and white bread, and leeks with sops and wine which represented a high-class version of a dish enjoyed by people from all backgrounds in the Middle Ages.

Peas Pottage

Pottage was a staple food for the everyman throughout history was a cross between soup, chowder and stew. Essentially it was a dish ate in a ‘pot’ or bowl and during the Medieval era consisted of foods slow-cooked until the broke down. Legumes, cereals, and if you were lucky, meat, was all used to make pottage. Peas pottage was probably the archetypal evening meal for a Medieval peasant. To make the pottage for the two of us we took 450g of peas, although other English beans could be used, two onions, a sprinkle of salt and sugar, and a spoon of oil (of course olive oil was not common in England but this isn’t going to affect the recipe dramatically). We put the peas and chopped in a pan heat them and to speed up the process we blended them, before adding them back to the pan with other ingredients. A pint of water was added, and this should all be cooked at lower heat until the pottage is thick and no longer watery. Although the result looks like mushy peas, it tasted much more like a pea and onion soup and was very hearty even by modern standards.

Cherry Pottage

This pottage was very different to the first, and was left to cool and set into a jelly-like pudding rather than a soup. However both are similar in that they are ideally a one-colour, homogenous bowl dish with no particular bits of food left distinguishable – ideal in the mind of someone alive 800 years ago. Cherry pottage contained white sugar and white bread so would’ve been a real delicacy probably only for nobility.

To make one pudding that serves two you will need three slices of bread crumbled into bread crumbs, two punnets of cherries (450g), 80g of sugar, 350ml of red wine, a pinch of salt, and 30g of butter. First remove stones from the cherries before adding them to a blender with the sugar. Then add this to a saucepan with the breadcrumbs and wine, as well as the sugar and butter. Simmer until it becomes very thick and similar to jam. Place in a bowl evenly and leave it to set, either in a fridge or naturally on the side whilst covered. To decorate you can sprinkle sugar over the top and even paint the ends of some cloves gold and balance them around the bowl to add some extra grandeur to this fine dish. It sets firm like jelly and is unrecognisable as the product of any of the whole ingredients. It’s very different to jam; more of a thick paste pudding/jelly, but well recommended. I was impressed how such a jelly-like dessert was made with the help of only sugar and bread.

Leeks and Sops in White Wine

Sops were essentially pieces of bread soaked in a soup-like liquid before being eaten. People of all classes would’ve enjoyed sops perhaps with pottage or any other cooked food and its juices. Even though this recipe is basic, white bread and white wine was reserved for upper classes, so a peasant would probably have eaten sops of brown bread with cooking juices rather than wine. Monks were said to officially have been able to eat stewed leeks cooked in water on white bread, but often deviated and ate them cooked in white wine.

To make two plates of the dish you will need half a bottle of white wine, a teaspoon of oil (your preference although olive oil was not common), a pinch of salt, four slices of white bread, and five leeks. Remove the tougher green parts of the leeks and simmer them in a pan until soft in the wine with the oil and salt added. When done pour the contents over the bread which should be broken into nugget-shaped pieces and scattered across a plate. The end result was pleasant; the white bread wasn’t too bad soaked in the juices, although the entire dish was pretty potent considering the sauce was made of dominantly wine.

That concludes our guide to Medieval food. Why not try changing the dishes? How about adding oats and bacon to the peas pottage, using apples and currants instead of cherries in the dessert pottage, or making a broth to eat with sops of brown bread? Hopefully the first part of the article should give you an idea of who ate what in the Middle Ages. Alternatively, get yourself a copy of the book that inspired our adventure; The Medieval Cookbook by Maggie Black.